Organism Cloning

When most people think of cloning, they usually think of Dolly the sheep, who in 1996 became the first mammal to be cloned from an adult cell2. Unfortunately, Dolly didn't live to a ripe old age, but her birth was an achievement and scientists have learned a lot through the process.

Breeding selected organisms for their desired traits has been going on for thousands of years. More recently, think back to good ol' Gregor Mendel and his peas. His controlled, selective breeding of pea plants was a form of genetic manipulation.

To start, here's a little terminology to make all of this a little easier to understand. A differentiated cell has reached its final destination and is specialized. It could be a skin cell, a liver cell, or a stinger cell in a bee. Some differentiated cells can become dedifferentiated and then coaxed in the lab to become a different type of cell. These cells are called totipotent.

You've probably heard of stem cells, if not through science classes, then through the media. Stem cells are cells that are not differentiated. They have the potential to become any type of cell. That's why they are like the holy grail of genetics.

Embryonic stem cells are pluripotent. They can become any type of cell. Adult stem cells cannot become all types of cells, but can give rise to many cell types. For this reason, embryonic stem cells are highly coveted. Their use does not come without difficult ethical issues, as we will discuss later.

Recently, scientists have learned how to convert differentiated cells into pluripotent cells. These cells are induced pluripotent cells (iPS).

Now that we have the terminology down, on to cloning we go. The first plant to be cloned from a single cell was a carrot. Yep, Bugs Bunny would be proud. Cells were taken from a carrot's roots by Charles Steward and his students in the 1950s and cultured in the lab. These cells eventually produced a plant. This showed that somehow adult plant cells could dedifferentiate and then result in all cell types of the plant. Pretty slick, Dr. Steward.

This method is used by many industries. Think about the lumber industry. What if we discovered a particular tree that was resistant to disease and could grow very tall and thick, and also enjoyed long walks on the beach? This could be a big money maker. We could take a sample and remove individual cells to grow in the lab. These cells can produce seedlings that can be transplanted into the ground. What's the end result of this hard work? Several trees genetically identical to the original tree.

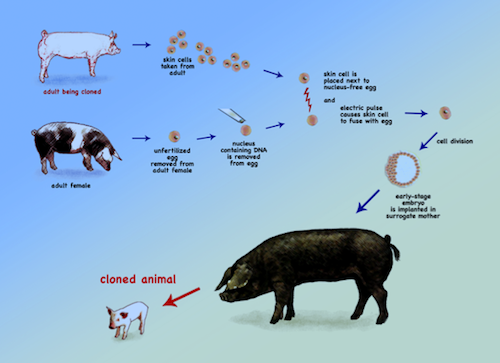

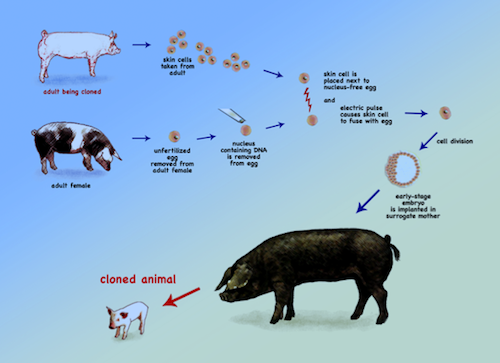

Animal cloning is a little different, and a little more complex. Animals cannot be cloned using the technique for plant cells because usually differentiated animal cells cannot be grown in culture. Instead, scientists use nuclear transplantion. Yep, it's just as it sounds. You've heard of heart and kidney transplants. In this case, the nucleus of a differentiated cell is inserted into a fertilized or unfertilized egg cell where the nucleus has been removed (or enucleated). The fertilized egg divides several times in the lab and become an embryo. The embryo is then implanted into a surrogate. The resulting animal is genetically identical to the organism whose nucleus was transplanted.

Image from here.

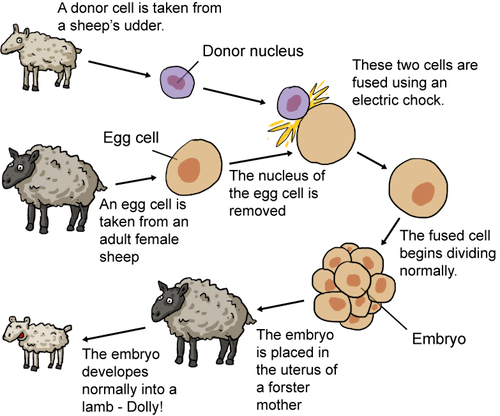

This technique was used to clone Dolly the sheep. Dolly was a super big deal. Scientists did not know whether or not an already differentiated cell could be used to clone an entire organism. A differentiated cell is already programmed to do its job. Could it direct development from the earliest stages?

The answer was yes, and Dolly was proof. Researchers developed a technique to dedifferentiate cells from six-year-old sheep udder tissue (mammary cells) in the lab. They then transferred these cells to sheep egg cells in which the nuclei had been removed. The cells were allowed to divide in the lab and eventually the embryos were implanted into surrogate female sheep. Dolly was the only live lamb born.

This achievement was monumental, but problems were soon discovered with Dolly. The normal lifespan of sheep is about twelve years. At the age of six, Dolly suffered from conditions normally seen in much older sheep and was euthanized. Scientists think poor Dolly's health problem could be because the nucleus used to clone Dolly was from a six year old sheep. If that doesn't belong in a sci-fi movie, we don't know what does.

Scientists have noticed that many cloned animals are prone to health issues. A closer look at the transplanted nuclei of several organisms suggests that they are not fully dedifferentiated. This could explain the premature aging and susceptibility to disease shown by cloned animals.

Cloning animals may be beneficial to the agricultural business, but what about human cloning? Scientists aren't as interested in creating another human being as generating stem cells from human embryos. Remember, embryonic stem cells can become any type of cell. They are not differentiated yet. These cells can be studied to better understand how a cell becomes differentiated. It is thought that they hold great promise for the treatment of medical conditions.

Image from here.

Breeding selected organisms for their desired traits has been going on for thousands of years. More recently, think back to good ol' Gregor Mendel and his peas. His controlled, selective breeding of pea plants was a form of genetic manipulation.

To start, here's a little terminology to make all of this a little easier to understand. A differentiated cell has reached its final destination and is specialized. It could be a skin cell, a liver cell, or a stinger cell in a bee. Some differentiated cells can become dedifferentiated and then coaxed in the lab to become a different type of cell. These cells are called totipotent.

You've probably heard of stem cells, if not through science classes, then through the media. Stem cells are cells that are not differentiated. They have the potential to become any type of cell. That's why they are like the holy grail of genetics.

Embryonic stem cells are pluripotent. They can become any type of cell. Adult stem cells cannot become all types of cells, but can give rise to many cell types. For this reason, embryonic stem cells are highly coveted. Their use does not come without difficult ethical issues, as we will discuss later.

Recently, scientists have learned how to convert differentiated cells into pluripotent cells. These cells are induced pluripotent cells (iPS).

Now that we have the terminology down, on to cloning we go. The first plant to be cloned from a single cell was a carrot. Yep, Bugs Bunny would be proud. Cells were taken from a carrot's roots by Charles Steward and his students in the 1950s and cultured in the lab. These cells eventually produced a plant. This showed that somehow adult plant cells could dedifferentiate and then result in all cell types of the plant. Pretty slick, Dr. Steward.

This method is used by many industries. Think about the lumber industry. What if we discovered a particular tree that was resistant to disease and could grow very tall and thick, and also enjoyed long walks on the beach? This could be a big money maker. We could take a sample and remove individual cells to grow in the lab. These cells can produce seedlings that can be transplanted into the ground. What's the end result of this hard work? Several trees genetically identical to the original tree.

Animal cloning is a little different, and a little more complex. Animals cannot be cloned using the technique for plant cells because usually differentiated animal cells cannot be grown in culture. Instead, scientists use nuclear transplantion. Yep, it's just as it sounds. You've heard of heart and kidney transplants. In this case, the nucleus of a differentiated cell is inserted into a fertilized or unfertilized egg cell where the nucleus has been removed (or enucleated). The fertilized egg divides several times in the lab and become an embryo. The embryo is then implanted into a surrogate. The resulting animal is genetically identical to the organism whose nucleus was transplanted.

Image from here.

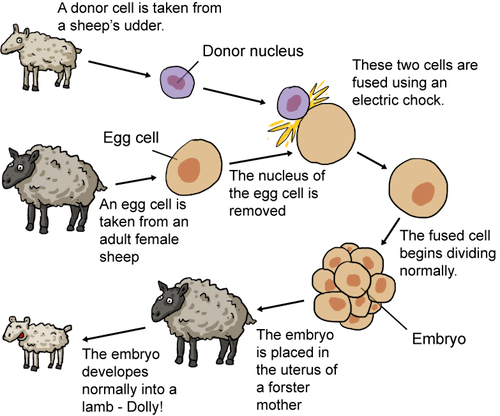

This technique was used to clone Dolly the sheep. Dolly was a super big deal. Scientists did not know whether or not an already differentiated cell could be used to clone an entire organism. A differentiated cell is already programmed to do its job. Could it direct development from the earliest stages?

The answer was yes, and Dolly was proof. Researchers developed a technique to dedifferentiate cells from six-year-old sheep udder tissue (mammary cells) in the lab. They then transferred these cells to sheep egg cells in which the nuclei had been removed. The cells were allowed to divide in the lab and eventually the embryos were implanted into surrogate female sheep. Dolly was the only live lamb born.

This achievement was monumental, but problems were soon discovered with Dolly. The normal lifespan of sheep is about twelve years. At the age of six, Dolly suffered from conditions normally seen in much older sheep and was euthanized. Scientists think poor Dolly's health problem could be because the nucleus used to clone Dolly was from a six year old sheep. If that doesn't belong in a sci-fi movie, we don't know what does.

Scientists have noticed that many cloned animals are prone to health issues. A closer look at the transplanted nuclei of several organisms suggests that they are not fully dedifferentiated. This could explain the premature aging and susceptibility to disease shown by cloned animals.

Cloning animals may be beneficial to the agricultural business, but what about human cloning? Scientists aren't as interested in creating another human being as generating stem cells from human embryos. Remember, embryonic stem cells can become any type of cell. They are not differentiated yet. These cells can be studied to better understand how a cell becomes differentiated. It is thought that they hold great promise for the treatment of medical conditions.

Image from here.