Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

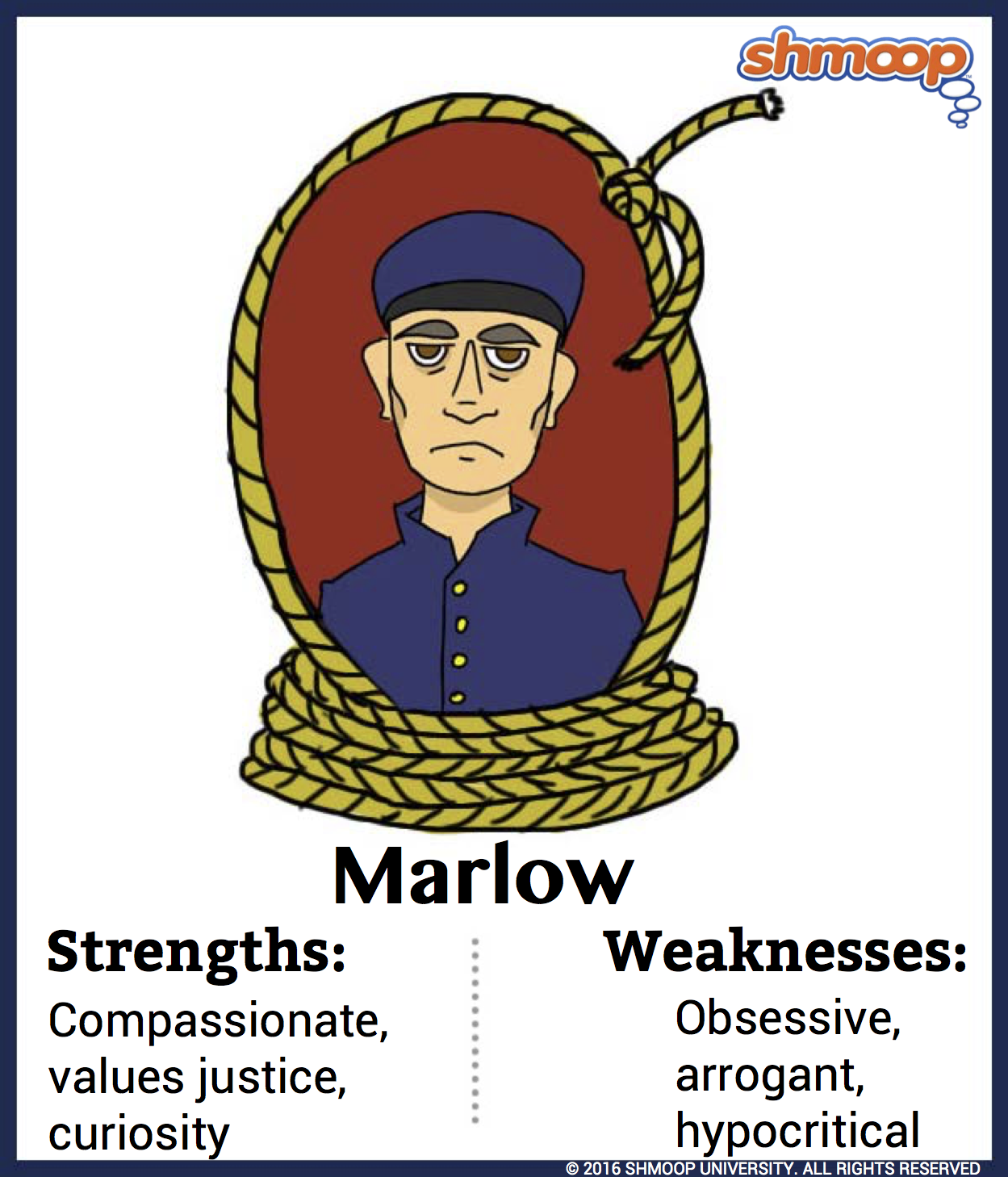

Marlow is a British seaman whose obsession with Africa brings him into the interior on the Company's steamboat.

Marlow and Kurtz

The way Marlow obsesses about Kurtz, we almost expect Kurtz to file a restraining order on the guy. (Or, we would if Kurtz weren't already half-dead by the time Marlow meets him.)

But it wasn't always like that. When Marlow first hears about Kurtz, he's not "very interested in him" (1.74). But when he hears the story about Kurtz turning back to the jungle, his ears prick up: he "[sees] Kurtz for the first time" (2.2) as a solitary white man among black men. And then, just a few paragraphs later, Marlow is actually excited to see the guy, saying that, for him, the journey has become entirely about meeting Kurtz. The boat, he says, "crawled towards Kurtz—exclusively" (2.7).

Weird. What was it about that story of Kurtz returning to the jungle that tickled Marlow's fancy? True, we've already seen that he's kind of obsessed with the jungle and its people. But at the same time he's drawn in by this primitive wilderness, he's terrified by it. It's thrilling but horrifying, kind of like Saw XVIII. (What, they haven't made that one yet?) Kurtz has done what Marlow can only dream of: refuse to return to the luxury and comfort of Europe and choose instead to pursue fortune and glory.

But Marlow's roller coaster of love doesn't doesn't end there. Once he actually meets the guy, he starts to resent him. Apparently, all that cultish adoration that the harlequin and the native Africans have for Kurtz turns Marlow's stomach: "He's no idol of mine" (3.6). And then he seems to decide that Kurtz is actually just childish—a helpless and selfish man who has ignorant dreams of becoming rich and powerful. (Note that when Marlow drags him back to the tent after Kurtz tries to escape, he's "not much heavier than a child" (3.29).)

Why the backpedaling? Well, we think that Marlow wants to differentiate himself from the brainwashed men around him—just like we claimed to hate Arcade Fire back in 2005 even though we secretly thought that Funeral was a great record. He also seems angry that he's effectively at Marlow's mercy, deep in the African interior. Or—to give Marlow some credit—maybe he really does believe that Kurtz is dangerous.

And then, at the end, Marlow seems to come back around to admiration. After Kurtz dies while gasping out the words "The horror! The horror!" (3.33), Marlow decides that these are words of self-realization, that maybe Kurtz has finally faced up to his horrible deeds and the depravity of human nature. "Kurtz was a remarkable man," Marlow says, because he "had something to say" and simply "said it" (3.48).

Marlow only spends a few days with Kurtz, but he still says that he "knew [Kurtz] as well as it's possible for one man to know another" (3.54). (Talk about a whirlwind romance.) But when Kurtz's Intended asks Marlow whether he admired Kurtz, Marlow never answers. We never find out what he would have said—but we do know that, when the fiancée suggests that Marlow loved the man, Marlow is left in "appalled dumbness" (3.57).

So, by the end of the story, does Marlow respect Kurtz? Admire him? Fear him? You tell us. He sure doesn't.

The Same But Different

This whole love me-love me not melodrama should be simple: Marlow admired Kurtz right up until he found out that the man put heads on sticks, at which point he stopped admiring him. Great. Let's all pack up and go home.

Er, not so fast. If you go home now, you'll you'll miss out on what makes Heart of Darkness just so darn awesome and powerful: Marlow is just like Kurtz. Yep: our protagonist, our loveable, sympathetic Marlow, is just like the crazed, cult-inspiring, heads-on-sticks-owning devil-man. Oh, the horror!

We'll start with the basics:

- Like Kurtz, Marlow comes from an upper middle class white European family.

- Both are, how do we say, arrogant: Marlow considers himself above the manager, the uncle, and the brickmaker while Kurtz establishes himself in an unparalleled seat of power among the native Africans.

- Both have streaks of obsession in them: Marlow becomes obsessed with Africa and finding Kurtz, while Kurtz stops at nothing to acquire as much ivory as possible.

- Both have powerful connections that allow them access to positions of power within the Company.

- Both men lose touch with reality—Kurtz in the fantasy of his own power and Marlow in the dream-like world of the jungle.

- Both men have eerily similar reactions to their forays to the interior of Africa. Marlow and Kurtz, despite their desire to conquer the wilderness, become victims of it: When Marlow observes native Africans dancing at the shore, he wonders why he doesn't go ashore "for a howl and a dance" (2.8). Later, he discusses Kurtz presiding over some "midnight dances" that ended in "certain unspeakable rites" (2.29).

- And finally, both men are described as gods—Kurtz as Jupiter and Marlow as Buddha (3.10, 3.87).

So, here's another million-dollar question for you: is Marlow ultimately able to differentiate himself from Kurtz?

Marlow and the Native Africans

For the most part, Marlow comes across as a nice guy, if not a particularly ethical one. He's no saint, or he's a helpless one, as he does nothing about the horrible scenarios of black slavery he encounters. But he does do little things that show compassion. He attempts to give a biscuit to a starving slave. He treats his own cannibals decently. When the helmsman dies, he makes sure he won't be ignobly eaten by the native Africans on board. So, on the surface level, Marlow is a decent guy who, as a product of his times, isn't about to start a civil rights movement in the late nineteenth century.

But, like most things in Heart of Darkness, it's really not that simple. What causes Marlow to feel such compassion for the native Africans? How does he see them in relation to himself? How does his foray down the Congo change the way he thinks?

Well, let's start by looking at his first word. We found these words so compelling that we underlined, highlighted, and circled them, as well as dog-earing the page and putting three sticky notes on the top. In case you weren't quite so over-zealous, we'll tell you straight-up that his first words are: "And this also has been one of the dark places of the earth" (1.8).

This is the part where we all say, "Oooh." Oooh indeed. Marlow is about to tell the story of a dark and primitive Africa which the Europeans are so kindly "civilizing." But he reminds you that Europe, too, was once a dark and primitive place.

From the start, Marlow takes this whole noble imperialism bit with a boulder of salt, telling his listeners that "strength is just an accident arising from the weakness of others" (1.12). He also notes that "This conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion […] than ourselves, is not a pretty thing" (1.12). He also questions everyone's use of words like "criminal," "enemy," and "rebel" in talking about the native Africans (3.6).

We know that Marlow isn't quite so comfortable with viewing the world in black and white. Things get even more complicated when he starts becoming like a "savage" himself. When he's talking to the manager at the outer station, Marlow is treated like a native African man—not offered a seat or any food. His response? "I was getting savage," he says, interrupting the man (1.53). Hmm. Rather than civilizing the "savages," it seems, Marlow is becoming like them.

Once he's underway, Marlow's attitudes get even fuzzier. When he looks at the native Africans dancing and howling, he doesn't see them as strange creatures. Instead, he says that they're "not inhuman" (2.8).

Interesting. Why not just say, "human"? Well, this is a nifty little device called "litotes." Marlow can't quite go so far as to call them human (as opposed to savage), so he says it more weakly by affirming its opposite. This sort-of-humanity is "thrilling," because it shows him that there's a "remote kinship" between him and the Africans (2.8)—the kinship of mortality. When the black helmsman dies, Marlow realizes that the "pilgrims" and the "savages" are linked by the one thing they have in common: mortality.

Freaky.

Marlow, Lies, and Justice

You might have noticed that Marlow makes a huge deal out of lies. He says he hates, detests, and can't bear a lie, that lies are reminiscent of death. So why does he lie to Kurtz's fiancée at the end of this whole story? Otherwise, "it would have been too dark" (3.86). Is he trying to protect the woman from the scary world of reality? Does he think that, by pretending the darkness and the horror of Kurtz's last words don't exist, they will somehow go away?

To have told the Intended the truth, he claims, would be to have "rendered Kurtz […] that justice which was his due" (3.86). After all, he tells us, Kurtz said that all he wanted was justice. What has justice come to mean in this novel, anyway? How can there be justice at all in a world where men put heads on sticks and are revered for it anyway?

You tell us.

All Hail Marlow

Conrad hints at some god-imagery when he has Marlow sits "cross-legged" like an "idol" (1.4). And then, in case we still don't get it, he straight out tells us Marlow was like Buddha (1.12). Oh, and in case we missed it the first time, he makes a big deal out of telling us at the end that Marlow sits like a "meditating Buddha " (3.87).

English-majory people would probably tell you that Conrad frames the story with a mention of Buddha at the beginning and then again at the end. To us, the point is that Marlow takes on the role of a spiritual figure, and specifically one whose role is to help other people reach enlightenment. But what does Marlow teach the men? Do the men get it? Is anyone enlightened by this tale?

One last thought: The nameless narrator tells us before the story begins that it will be an inconclusive tale. Does this fit with the Buddha imagery, or stand in contrast to it? What kind of teacher is inconclusive, anyway? (Did you notice that we're ending this section inconclusively?)

Curiosity Killed the Cat

As a kid, Marlow wanted to map the uncharted blank spaces on maps and to explore the "blankest" and most unknown of all places—Africa (1.16). No wonder that, as an explorer for the Company, he becomes curious about Kurtz—so curious that he's willing to listen in on private conversations and even sacrifice some of his men along the way. To us, it seems like Conrad might be suggesting there's something a little unethical about the very act of exploration. Whether you're trying to fill in blank spaces on a map or blank spaces in a person's mind (like with a novel), you're always looking into something you shouldn't.

Interestingly, because of Marlow's story-telling tendencies, we experience events the way he did: with much confusion and fog, both literal and metaphorical. When he starts ruminating on past events, our nameless narrator tells us that Marlow is not a typical seaman. He's a "wanderer" (1.9), and he tells his story as if the meaning is "outside" of the tale, brought out "as a glow brings out a haze" (1.3).

Hmm…are you curious yet?

Marlow and The Laaadies

Marlow may have a thing for mysterious, amoral men—but he doesn't seem to think much of women. Twice in the novel, he mentions women and always sees them as somehow divorced from reality, as living in another world: "It's queer how out of touch with truth women are," he says: "They live in a world of their own, and there has never been anything like it, and never can be. It's too beautiful all together" (1.28). (Um, Marlow? If women literally make up half the world, then who's to say that their world isn't the "real" one?)

Anyway, Marlow obviously sees women as naïve and idealistic. But here's the rub: he wants them to stay that way. When he lies to Kurtz's Intended, it looks a lot like a chivalrous attempt to protect women from the world's brutal realities—like slavery and imperialism. Well, except for those two knitting women in black, who seem to have a weird power over Marlow—almost like they might be representations of fate, knitting up his destiny. Women: pure and evil all at once.

From our position, that contradiction seems like a pretty good way to sum op Mr. Marlow.

Charlie Marlow's Timeline