Character Analysis

Elizabeth Bennet may not look much like Frodo Baggins, but a ring is central to her quest, too. Marriage is the key to happiness—or at least that's what she hears from nearly everyone around her. As the second daughter of a country gentleman who can't leave his estate to a girl (and who forgot to stock his 401k), Elizabeth is headed straight for poverty if she doesn't marry a man who can provide for her.

Still, Elizabeth has eyes as well as ears. In fact, she prides herself on being a good observer, and she's observed that marriage can also be a one-way ticket to unhappiness. Despair if you do, despair if you don't. Which way to Mount Doom?

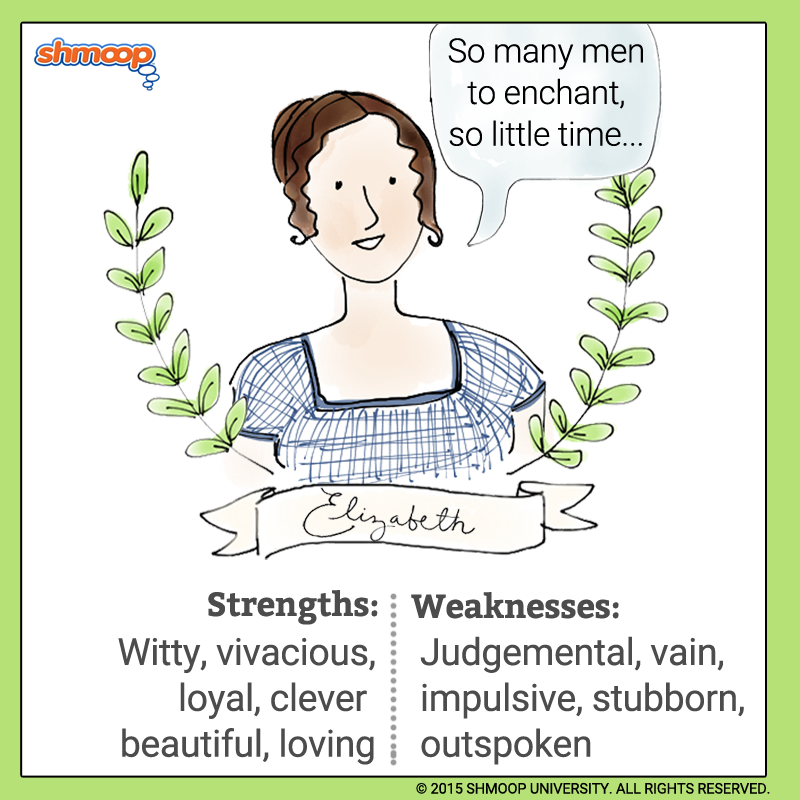

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Funny Girl

When we meet Lizzy Bennet, she seems awesome: smart, funny, pretty, and loyal. (In fact, we'd want her to be our BFF if we weren't pretty sure that she'd turn us down.) Austen tells us that "she had a lively, playful disposition, which delighted in anything ridiculous" (3.14). And it's true.

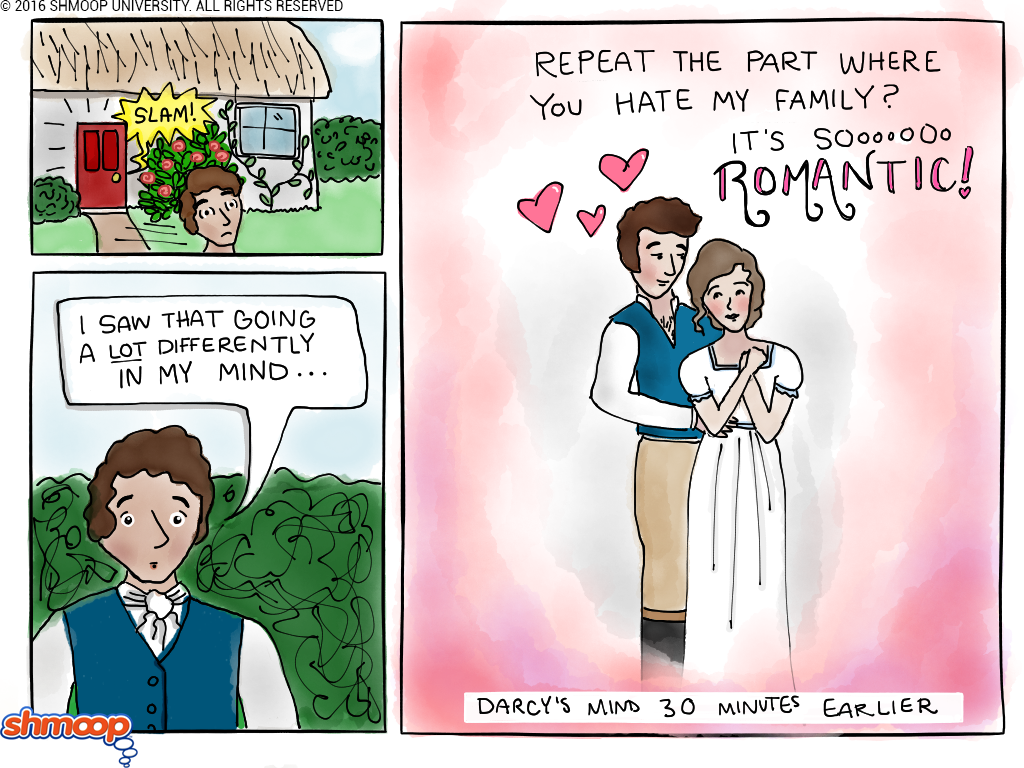

The problem is that not everyone gets her sense of humor. Sometimes that's good, like when she's making fun of Mr. Collins to his face. And sometimes it just leads to misunderstandings, like when she tells Mr. Darcy that she "rather wonder[s] now at [his] knowing any" accomplished women (8.51-52). She's making fun of the ridiculous standards that he and Miss Bingley have come up with for accomplishment, but she's the only one laughing.

Lizzy can't even be serious with her sister—or, to be honest, with us. When Jane asks how long she's loved Darcy, she says, "It has been coming on so gradually, that I hardly know when it began. But I believe I must date it from my first seeing his beautiful grounds at Pemberley" (59.16).

On the one hand, she's joking by making herself seem like a gold-digger who loves Darcy's estate and money, and not him. On the other hand—it's kind of true. She did have a change of heart at Pemberley. Lizzy's constant joking makes her character a little hard to read, like that friend who can never tell you straight up how she feels. Learning to be straightforward with Darcy (and herself) is one of the many changes she undergoes.

Her Eyes Were Watching You

Elizabeth also prides herself on being a good judge of character. (This from a girl who's twenty years old, mind you.) And she is good at reading situations. When she watches Mr. Collins sidle up to Mr. Darcy, she can tell how it's going even from across the room:

And with a low bow he left her to attack Mr. Darcy, whose reception of his advances she eagerly watched, and whose astonishment at being so addressed was very evident. […] Mr. Collins, however, was not discouraged from speaking again, and Mr. Darcy's contempt seemed abundantly increasing with the length of his second speech, and at the end of it he only made him a slight bow, and moved another way. (18.57)

Mr. Collins is right there next to him, but he's so self-absorbed that he can't see how much Darcy despises him. Not Lizzy, who can see exactly what's going on. She's right a lot of the time, like when she tells Jane that Miss Bingley "follows [Bingley] to town in hope of keeping him there, and tries to persuade you that he does not care about you" (21.19). And she's right again when she sees that Darcy "had no doubt of a favourable answer" during his first proposal (34.6).

But Lizzy isn't always right, and that's the hard lesson she has to learn. All it takes to blind her powers of observation is a pretty face. Let's look at the moment that happens.

The Change

After Lizzy reads the letter in which Darcy explains the Wickham situation, she spends a lot of time berating herself for her actions:

She grew absolutely ashamed of herself. Of neither Darcy nor Wickham could she think without feeling she had been blind, partial, prejudiced, absurd.

"How despicably I have acted!" she cried; "I, who have prided myself on my discernment! I, who have valued myself on my abilities! who have often disdained the generous candour of my sister, and gratified my vanity in useless or blameable mistrust! How humiliating is this discovery! Yet, how just a humiliation! Had I been in love, I could not have been more wretchedly blind! But vanity, not love, has been my folly. Pleased with the preference of one, and offended by the neglect of the other, on the very beginning of our acquaintance, I have courted prepossession and ignorance, and driven reason away, where either were concerned. Till this moment I never knew myself." (36.18-19)

Notice that sentence at the end, "'Till this moment I never knew myself"? That's some character growth, right there. Lizzy is admitting that she was "prejudiced" (ahem, title alert): she let Wickham's pretty face and charming manners make up for the fact that he behaved totally inappropriately, and she let Darcy's bad manners—which, admittedly, were pretty bad—convince her that he was actually a bad person.

In fact, the whole second half of the novel is full of these moments of self-revelation. When Lydia makes some snide comments about Wickham's new flame, calling her a "nasty little freckled thing" (39.14), Lizzy has to admit that she's no better than her sister: although she is "incapable of such coarseness of expression herself, the coarseness of the sentiment was little other than her own breast had harboured and fancied liberal!" (39.13-15).

And then, you know how sometimes you can't help lying in bed and thinking about all the humiliating things that you've done? (Just us?) Lizzy has the same problem: "In her own past behavior, there was a constant source of vexation and regret" (37.17). In plain English, she's embarrassed. All the time.

But a little embarrassment turns out to be a good thing, since Lizzy learns to temper her behavior a little bit—not when in comes to important things, like being true to her own convictions about what's right—but when it comes to things like paying attention to her future husband's feelings. After they've finally cleared up all misunderstandings, she's dying to tease him about Bingley, but stops herself: "she remembered that he had yet to learn to be laughed at, and it was rather too early to begin" (58.46).

Good move, Lizzy.

True Romantic

And now let's settle something. Jane Austen has a reputation for writing romances, right? And Lizzy is one of her heroines, so she must be romantic. Right? Well, maybe. We never learn exactly what she thinks about marriage and love, but we can certainly deduce a few things.

First, she certainly doesn't believe that it should just be a matter of "worldly advantage" (22.18). At the same time, she's not about to marry an unreliable flirt like Wickham just because she wants to hop into bed with him. (That's what Mr. and Mrs. Bennet did, and you can see how well that worked out.) She'd also never marry a poor man: she tells her aunt that she has come to "the mortifying conviction that handsome young men must have something to live on as well as the plain" (26.28). Typical Lizzy, she makes a joke out of it—but that doesn't change the fact that it's true.

So let's see what she thinks when she realizes that she does want to marry Darcy after all:

She began now to comprehend that he was exactly the man who, in disposition and talents, would most suit her. His understanding and temper, though unlike her own, would have answered all her wishes. It was a union that must have been to the advantage of both; by her ease and liveliness, his mind might have been softened, his manners improved; and from his judgement, information, and knowledge of the world, she must have received benefit of greater importance. (50.15)

Do you see the word "love" anywhere in this passage? Nope. A marriage needs "true affection" (18.56), and Lizzy does love Darcy, but that's not what matters. What's really important for the success of this marriage is that (1) she respects him; (2) they complement each other; and (3) they can support themselves.

This is key. Austen is writing at a time when new ideas about companionate marriage and love (rather than just financial security and passing along the estate) were becoming more common, but financial security and the estate still mattered. The traditional, practical, loveless marriage may have been starting to look like a weird form of human trafficking, but Austen definitely wasn't saying that we should all run off with the love of our lives. Notice how Lizzy and Colonel Fitzwilliam don't end up together, even though we all kind of want them to? He can't support her—but Darcy can.

See, Austen isn't promoting the romantic love we're more familiar with, the "who cares about our parents or our gigantic student loan debts; we're meant to be together 4EVA." Lizzy and Darcy may not be exactly soulmates in the way we think about soulmates, but they certainly are lifemates: they're both willing to work hard for their marriage and their family.

Elizabeth Bennet's Timeline