Let the Food Come to Them

It's alive! Sponges are animals, the oldest ones around.

The first branching in the animal family tree is the split between the parazoa and eumetazoa. The difference between these two groups of animals is the presence of real tissues. This does not mean one group is prepared for sneezes and the other isn't. A tissue, in this case, is a group of cells with the same structure that work together for a purpose. For instance, muscle cells have their own unique structure and work together to form the muscle tissue that moves animals.

Image from here.

Porifera, or sponges, is the one phylum in the group parazoa. They are made up of cells, but some cells in a sponge can move around and even change form. The cells are not bound together, unlike cells that are part of true tissues.

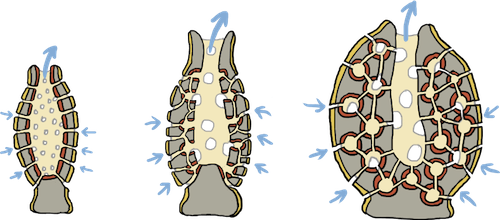

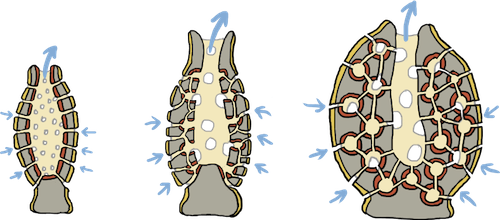

The basic structure of a sponge is an asymmetrical sack with a large opening and lots of small pores. Forget SpongeBob. Sponges don't even have a mouth. Sponges are suspension feeders, which means that they take in the nutrients floating in water. Water flows into a sponge through its pores and is moved through the sponge by flagella, a special extension of some cells that acts like a whip, moving water through the sponge. This keeps water moving in one direction. Water moving out of the sponge takes out waste.

Porifera Body

Just like the sponge on the kitchen sink, sponges only work in water. Most are in the oceans. On the outside, sponges do resemble plants in that they are sessile. This means that like a houseplant, sponges sit still. A sponge has only a few short days of floating free when it first hatches. After that spree, a sponge larva anchors itself and begins to grow.

Sponges are not as simple as they may look, however, particularly when it comes to reproduction. (Never a simple process, right?) Sponges reproduce both sexually and asexually. Sponges can regenerate lost parts and use this same power to produce offspring asexually. Sponges are also usually hermaphrodites, which means that every sponge has the ability to produce both male and female gametes. What they lack in flash, sponges make up for in reproductive versatility.

The first branching in the animal family tree is the split between the parazoa and eumetazoa. The difference between these two groups of animals is the presence of real tissues. This does not mean one group is prepared for sneezes and the other isn't. A tissue, in this case, is a group of cells with the same structure that work together for a purpose. For instance, muscle cells have their own unique structure and work together to form the muscle tissue that moves animals.

Image from here.

Porifera, or sponges, is the one phylum in the group parazoa. They are made up of cells, but some cells in a sponge can move around and even change form. The cells are not bound together, unlike cells that are part of true tissues.

The basic structure of a sponge is an asymmetrical sack with a large opening and lots of small pores. Forget SpongeBob. Sponges don't even have a mouth. Sponges are suspension feeders, which means that they take in the nutrients floating in water. Water flows into a sponge through its pores and is moved through the sponge by flagella, a special extension of some cells that acts like a whip, moving water through the sponge. This keeps water moving in one direction. Water moving out of the sponge takes out waste.

Porifera Body

Brain Snack

Check out this exception to suspension-feeding sponges. Scientists not long ago discovered sponges that eat whole organisms. Brushing up against these quiet creatures leads to a slow death.Just like the sponge on the kitchen sink, sponges only work in water. Most are in the oceans. On the outside, sponges do resemble plants in that they are sessile. This means that like a houseplant, sponges sit still. A sponge has only a few short days of floating free when it first hatches. After that spree, a sponge larva anchors itself and begins to grow.

Sponges are not as simple as they may look, however, particularly when it comes to reproduction. (Never a simple process, right?) Sponges reproduce both sexually and asexually. Sponges can regenerate lost parts and use this same power to produce offspring asexually. Sponges are also usually hermaphrodites, which means that every sponge has the ability to produce both male and female gametes. What they lack in flash, sponges make up for in reproductive versatility.