Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

An Everywoman

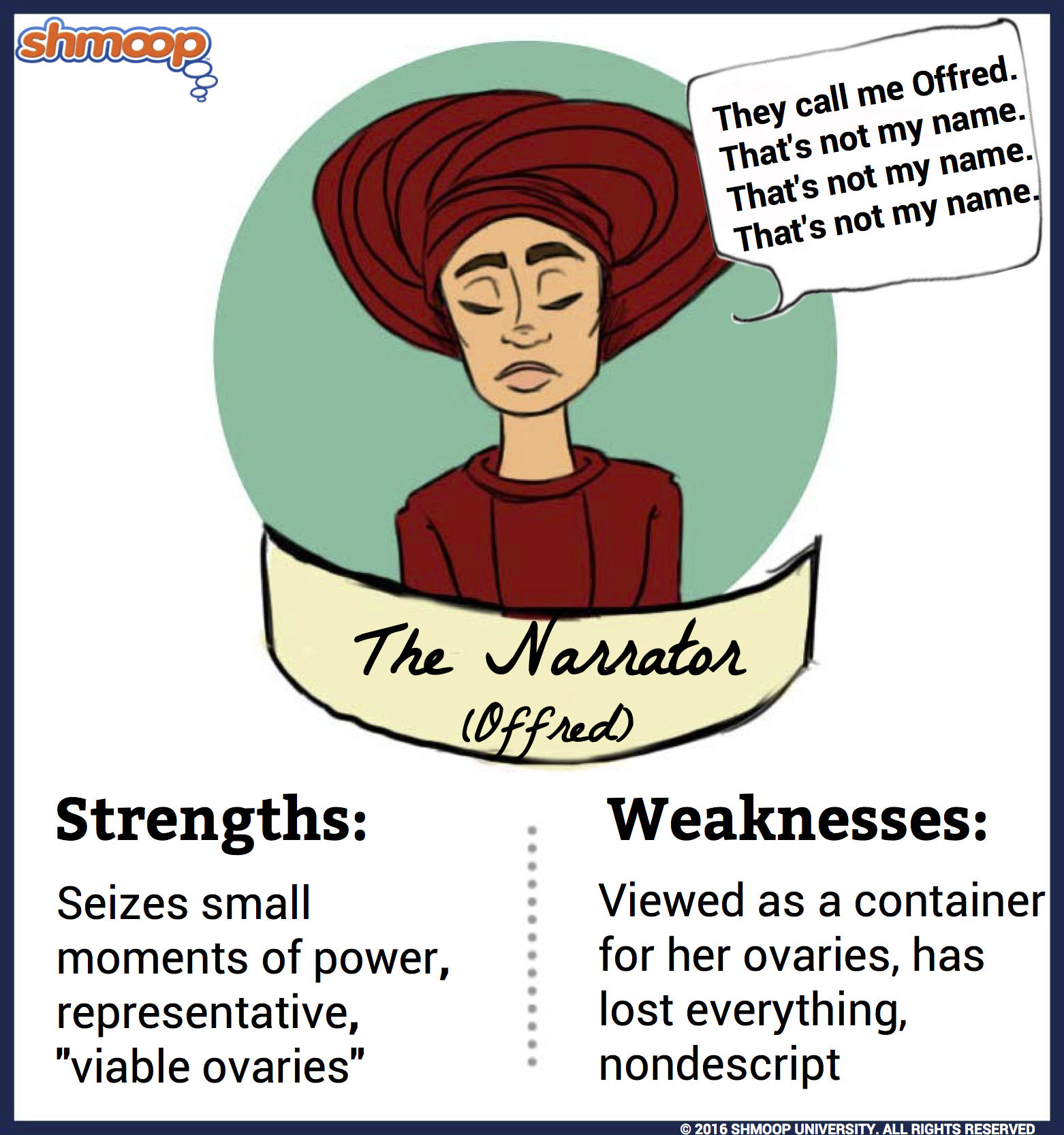

The narrator is definitely the most significant character in the novel—she's the Handmaid telling this tale, and we experience the world of Gilead through her eyes. But how well do we really know her? Answer: um, not all that well.

Isn't it kind of odd that we know she has "viable ovaries," but we don't know what her real name is or what she looks like? Even when we finally hear a name given to her by another character, she's quick to disregard it:

My name isn't Offred, I have another name, which nobody uses now because it's forbidden. (14.37)

(Out of respect for her, we here at Shmoop consistently refers to her as "the narrator" because, as she says, Offred's not her real name.) But, it's hard to feel very close to someone when even her name is kept a secret. We know about her relationships from the time before, about her small wants and desires, and about the way she faces this new world in a manner that's both reckless and terrified. That doesn't make it easy, though, to picture the narrator's face. We get very few physical details from her, apart from the following:

I am thirty-three years old. I have brown hair. I stand five seven without shoes. I have trouble remembering what I used to look like. I have viable ovaries. I have one more chance. (24.6)

Some facts remain to the narrator—age, hair color, height—but she doesn't mention eye color or any other details about her body. She says she "ha[s] trouble remembering what [she] used to look like," and she's not even able to look in mirrors anymore. She can't see herself, just like we can't see her.

More important in this society than any of these appearance-based details, it seems, is internal physicality. The narrator has "viable ovaries," and that's what's kept her alive and relatively out of danger all this time. But society treats her like a mere container for those ovaries, and her expiration date is looming. The idea that she has "one more chance" now defines her as much as her having "brown hair."

So despite spending all this time in the narrator's head, we really don't know much about her. As Professor Pieixoto wonders in the "Historical Notes":

But what else do we know about her, apart from her age, some physical characteristics that could be anyone's, and her place of residence? Not very much. She appears to have been an educated woman, insofar as a graduate of any North American college of the time may be said to have been educated. [...] But the woods, as you say, were full of these, so that is no help. (Historical Notes.29)

But the fact that the narrator is so nondescript allows her to represent every woman who's been forced into the position of Handmaid in this society. Even though her frequent flashbacks give us glimpses of her former life, the Center has had a real effect on her. Everything she says is protected by a pseudonym.

An Individual

But some of her smallest asides reveal ways in which she holds on to her individuality. For example, she's not a crybaby suck-up like Janine. She's also not an out-and-out rebel like Moira. However, she does take small pleasures from manipulating her world in the little ways she can—like taking small digs at the men who have power over her. One day, for instance, she makes eye contact with a Guardian when she's out shopping, even though Guardians are strictly forbidden from looking at Handmaids:

It's an event, a small defiance of rule, so small as to be undetectable, but such moments are the rewards I hold out for myself, like the candy I hoarded, as a child, at the back of a drawer. (4.47)

Her world has become tiny and her identity stolen from her, but she still clings to small elements of what make her herself, such "hoard[ing]" just as she did when she was little.

The narrator frequently contemplates stealing things, too. She envisions stealing from the Commander's household as a way to take back her power, and one of her most frequent fantasy objects is a weapon. But she's not reckless, either: she rejects even stealing a daffodil from Serena Joy's flower arrangement. The closest she comes to theft is sneaking pats of butter from her plate to use as lotion, or hiding the match that should have lit her single cigarette.

Her Past Life

The narrator regrets the absence of mundane things, like being able to do laundry or have silly fights with her husband. The trivial things from her previous life have now become profound:

I think about Laundromats. What I wore to them: shorts, jeans, jogging pants. What I put into them: my own clothes, my own soap, my own money, money I had earned myself. (5.9)

Such a simple act as doing laundry represents a level of freedom that would be unthinkable now that the Republic of Gilead has taken all autonomy and control away from her.

The narrator's thoughts often turn to her lost husband. For example, when the doctor offers her "help" at her monthly appointment, her first thought isn't that he could help her get pregnant (which is what he means). She hopes he has news about her hubby:

Does he know something, has he seen Luke, has he found, can he bring back? (11.15)

Despite her deep hope that she'll see Luke again, she begins to wonder more and more—in spite of herself—whether he's dead. She worries that she has betrayed him, alive or dead, by having sex with Nick. The chances of her ever meeting Luke again are slim, but she still holds on to the idea of their relationship.

Mama Bear

Oh—and let's not forget about the fact that even though the narrator's role in society requires her to constantly obsess about getting pregnant, she's already a mother. Yet she's been completely severed from her daughter. And it doesn't seem like there's much of a chance of getting her back. Sometimes it seems like it's easier for the narrator to believe that her daughter is dead, but other times she hopes against hope that her daughter is alive:

I [...] think about a girl who did not die when she was five; who still does exist, I hope, though not for me. Do I exist for her? Am I a picture somewhere, in the dark at the back of her mind? [...] Eight, she must be now. I've filled in the time I lost, I know how much there's been. They were right, it's easier, to think of her as dead. I don't have to hope then, or make a wasted effort. (12.13, 15)

The narrator prays her daughter is alive, and wonders whether her daughter even remembers her. At the Center the Aunts taught the Handmaids to consider their children dead. The narrator acknowledges that this is "easier" because it saves her from the cruelty of hoping in what seems like a vacuum. Yet she keeps believing in her daughter's potential existence.

Later in the book the narrator is presented with seeming proof that her daughter is alive when Serena Joy brings her a Polaroid picture in exchange for her agreeing to have sex with Nick to try to increase her odds of pregnancy. At first, she feels relief and joy about seeing her daughter, her "treasure" (35.33), alive. But her relief quickly turns to distress as she realizes that her little girl is someone else's child, that society has been able to fool her daughter into forgetting her birth mother:

I have been obliterated for her [...]. You can see it in her eyes: I am not there [...] I can't bear it, to have been erased like that. Better she'd brought me nothing. (35.35, 37)

It's heartbreaking that even this last connection with her child has been taken from her. Given her tremendous loss, it's no wonder the narrator would go willingly with the men in the black van at the end of the book, even if they aren't resistance workers. She's already lost everything; now all she has to go on is hope.

The Narrator's Timeline