What's So Special About Speciation?

Now that we're armed with the BSC, we can finally explore Speciation—the evolutionary process that leads to the generation of multiple species from a single common ancestor. We have speciation to thank for the Earth's incredible biodiversity: one million species of mites (yes, we know you’re drafting speciation a thank you note right now), up to 30 million insect species (putting a stamp on the envelope), more bacteria than we can imagine, 270,000 plant species, and about 56,000 species of vertebrates. The numbers are staggering and growing all the time.

The study of speciation starts with the question: how does one species split to become two? As we approach this question, it's important to think about how lineages change in general. Even in the absence of speciation, species don't just sit around, staying the same and waiting for some evolutionary action to pick up. They're usually gradually changing and adapting to their environment, which is also changing. For example, Mr. Potato head might respond to some mating cue or environmental pressure over time to slowly change color. This potato species isnt speciation—it's still all one species—but it is evolving.

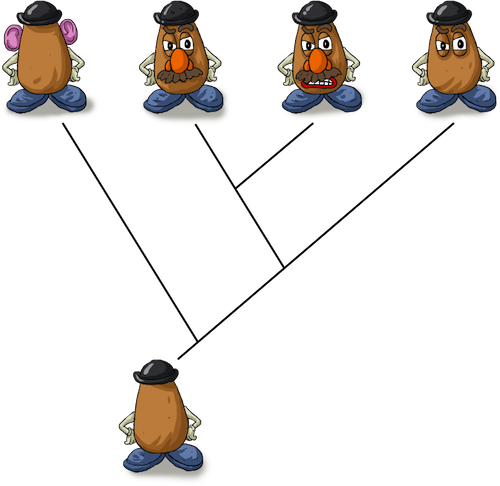

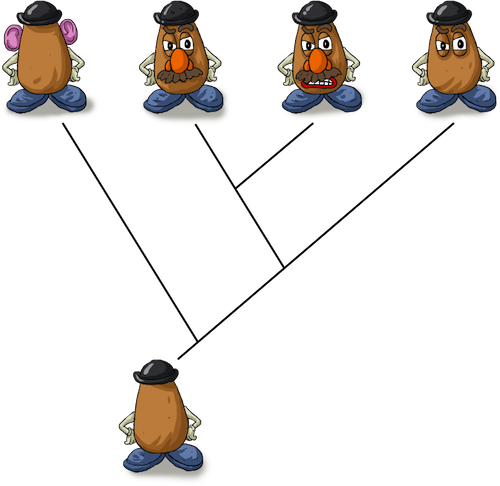

Now it's helpful to look at a phylogenetic tree like the one below. There are two important parts we want to point out: the branches themselves (at the ends of which we list species), and the nodes where one branch splits into two. Throughout the entire tree, organisms are changing and evolving. The two different parts—branches and nodes—represent two different types of evolution: anagenesis and cladogenesis.

The evolutionary change that occurs within a branch is called anagenesis, demonstrated by our first potato head example. The changes could be new mutations, lost alleles, and changes in gene frequencies, but all the organisms in that branch still belong to the same species. At the nodes, cladogenesis is occurring. In cladogenesis something happens that results in the splitting of two new species. The two branches now represent distinct species that will undergo their own separate evolutionary paths (via anagenesis), until another speciation event occurs (cladogenesis).

That's cool, but…what's going on in cladogenesis that makes it so wildly different from anagenesis? It all comes down to gene flow, and a better way to look at the tree above would be to zoom in on the actual genes that are being passed down, because after all, species are just big packages of genes. The following image shows the actual genes of a species that is polymorphic for a given allele, and the two alleles are depicted by orange and blue. In generations 1-3, genes are shared among individuals and the species remains one. However, in generation 4-5 gene flow is disrupted. Gene flow is no longer possible among all members of the species, but only among members belonging to two distinct subgroups. With drift and selection acting on these groups independently, and with no sharing of genes between them, what was once one gene pool now branches into two.

During periods of anagenesis, gene flow is unrestricted. One individual might have very different genes from another individual, but they belong to the same gene pool and could theoretically mate to produce an offspring that shared both their genes.

In periods of cladogeneis, though, everything's fine and dandy in the gene pool. Then something happens that disrupts gene flow. Cannonball? This is the beginning of speciation. What used to be one big happy gene pool begins to split into two kiddie pools, each with different allele frequencies and very little genetic exchange between them. Voilà. What was once one species becomes two.

Maybe not quite "voilà." We still haven't identified the mechanism that isolates the two kiddie pools in the first place. A force that prevents reproduction between them is as coming into play. The fancy name for it is reproductive isolation.

The study of speciation starts with the question: how does one species split to become two? As we approach this question, it's important to think about how lineages change in general. Even in the absence of speciation, species don't just sit around, staying the same and waiting for some evolutionary action to pick up. They're usually gradually changing and adapting to their environment, which is also changing. For example, Mr. Potato head might respond to some mating cue or environmental pressure over time to slowly change color. This potato species isnt speciation—it's still all one species—but it is evolving.

Now it's helpful to look at a phylogenetic tree like the one below. There are two important parts we want to point out: the branches themselves (at the ends of which we list species), and the nodes where one branch splits into two. Throughout the entire tree, organisms are changing and evolving. The two different parts—branches and nodes—represent two different types of evolution: anagenesis and cladogenesis.

The evolutionary change that occurs within a branch is called anagenesis, demonstrated by our first potato head example. The changes could be new mutations, lost alleles, and changes in gene frequencies, but all the organisms in that branch still belong to the same species. At the nodes, cladogenesis is occurring. In cladogenesis something happens that results in the splitting of two new species. The two branches now represent distinct species that will undergo their own separate evolutionary paths (via anagenesis), until another speciation event occurs (cladogenesis).

That's cool, but…what's going on in cladogenesis that makes it so wildly different from anagenesis? It all comes down to gene flow, and a better way to look at the tree above would be to zoom in on the actual genes that are being passed down, because after all, species are just big packages of genes. The following image shows the actual genes of a species that is polymorphic for a given allele, and the two alleles are depicted by orange and blue. In generations 1-3, genes are shared among individuals and the species remains one. However, in generation 4-5 gene flow is disrupted. Gene flow is no longer possible among all members of the species, but only among members belonging to two distinct subgroups. With drift and selection acting on these groups independently, and with no sharing of genes between them, what was once one gene pool now branches into two.

During periods of anagenesis, gene flow is unrestricted. One individual might have very different genes from another individual, but they belong to the same gene pool and could theoretically mate to produce an offspring that shared both their genes.

In periods of cladogeneis, though, everything's fine and dandy in the gene pool. Then something happens that disrupts gene flow. Cannonball? This is the beginning of speciation. What used to be one big happy gene pool begins to split into two kiddie pools, each with different allele frequencies and very little genetic exchange between them. Voilà. What was once one species becomes two.

Maybe not quite "voilà." We still haven't identified the mechanism that isolates the two kiddie pools in the first place. A force that prevents reproduction between them is as coming into play. The fancy name for it is reproductive isolation.