Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

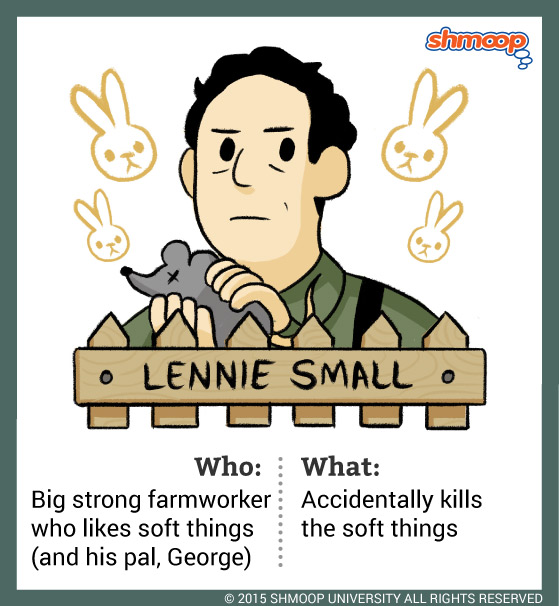

Don't let the name fool you: Lennie Small is big. Unfortunately, that's about all he has going for him—that, and he's got a really good friend. So, what did Lennie do to deserve a friend like George?

Lennie and George

When we first meet Lennie and George, we almost can't tell them apart: "Both were dressed in denim trousers and in denim coats with brass buttons. Both wore black, shapeless hats and both carried tight blanket rolls slung over their shoulders" (1.4). They're two itinerant farmworkers, looking for work wherever they can. From a distance, there's nothing to tell either apart. But when we get closer, we see that this isn't a relationship of equals:

Lennie, who had been watching, imitated George exactly. He pushed himself back, drew up his knees, embraced them, looked over to George to see whether he had it just right. He pulled his hat down a little more over his eyes, the way George's hat was. (1.10)

If this reminds you of a kid imitating his dad, then you're on the right track: from these few sentences, we know that something is seriously wrong with Lennie. Like a kid, he mournfully wishes for ketchup to put on his beans; like a kid, he demands a bedtime story—even when he knows it all himself: "No…you tell it. It ain't the same if I tell it. Go on…George. How I get to tend the rabbits" (1.121).

We don't know exactly what the problem is, but we know that Lennie has a serious mental disability. He can't remember anything; he fixates on things like owning rabbits; and he's painfully eager to make George happy. He even gives away all of the (imaginary) ketchup: "But I wouldn't eat none, George. I'd leave it all for you. You could cover your beans with it and I wouldn't touch none of it" (1.93-95).

This still doesn't help us figure out why Lennie gets a friend like George. In fact, it seems like Lennie shouldn't have many friends at all—even George thinks he's a little annoying. Lennie almost gets it: "I got you to look after me, and you got me to look after you" (1.115). What Lennie doesn't quite understand is that Lennie provides a need. He needs to be looked after, and George needs someone to care for.

Sure, it might sound like co-dependency. But for guys like Lennie and George, co-dependency is all that's keeping them from the whorehouses—or the asylum.

Can't We All Just Get Along?

Lennie also adds a daily dose of sunshine to George's life, even if George doesn't seem too grateful. He's always talking "happily" (1.7) or "delightedly" (1.115), because he never understands when a situation is serious. Even when George is yelling at him not to drink too much, he says, "Tha's good … You drink some, George. You take a good big drink" (1.7).

Because he doesn't understand all the nasty currents of the adult world, Lennie is an innocent. All he wants is for George to be nice to him, and to pet soft things.

And about that obsession with soft things: Lennie just can't keep his hands to himself. He likes to pet rabbits and mice and puppies and women's dresses, which is problematic when they end up (1) dead or (2) accusing him of rape. The thing is, we're not sure exactly how innocent Lennie is. He stares at Curley's wife when she struts around the ranch, even though George tells him to stay away. All the animals he pets ends up dead, so he can't be all that gentle. And his obsession with rabbits is—we'll say it—a little creepy.

We don't think Lennie is malicious. Like Slim, we're pretty sure he "ain't mean" (3.28). But we're also not sure he's just supposed to be a gentle giant. The mice don't die accidentally—they die because Lennie "pinched their heads a little" after they bit him (1.79). He says, "they was dead—because they was so little," but their size doesn't really have anything to do with it. They're dead because Lennie retaliated. Could he represent the unthinking violence that all men are capable of? The brute human nature lurking beneath even guys like George and Slim?

Big Baby

Lennie dimly understands that something is wrong with him, and that's exactly why he wants rabbits, because "they ain't so little" (1.79). If he pinches their heads, they'll survive. But he's still pinching their heads, and he's still basically torturing the animals that he's supposed to be looking after.

George insists that he's "jes like a kid," and that "There ain't no more harm in him than a kid neither, except he's so strong" (3.44-45). But regardless of what Lennie means to do, he's not a kid: he's a dangerous man. George tries to put a good spin on it, saying "That mouse ain't fresh, Lennie; and besides, you've broke it pettin' it. You get another mouse that's fresh and I'll let you keep it a little while" (1.76).

The problem is, the mouse isn't a product that can be "fresh" or "broke." George may be trying to protect Lennie, but in the process he's exposing all sorts of living creatures to Lennie's casual violence. Lennie may only want to be loved and surrounded by soft things, but that's still too much. In the harsh, Depression-era world of the novel, Lennie simply doesn't get to have what he wants, because it's too dangerous. In the end, death is the only option—or at least the most merciful one.

Lennie's Timeline