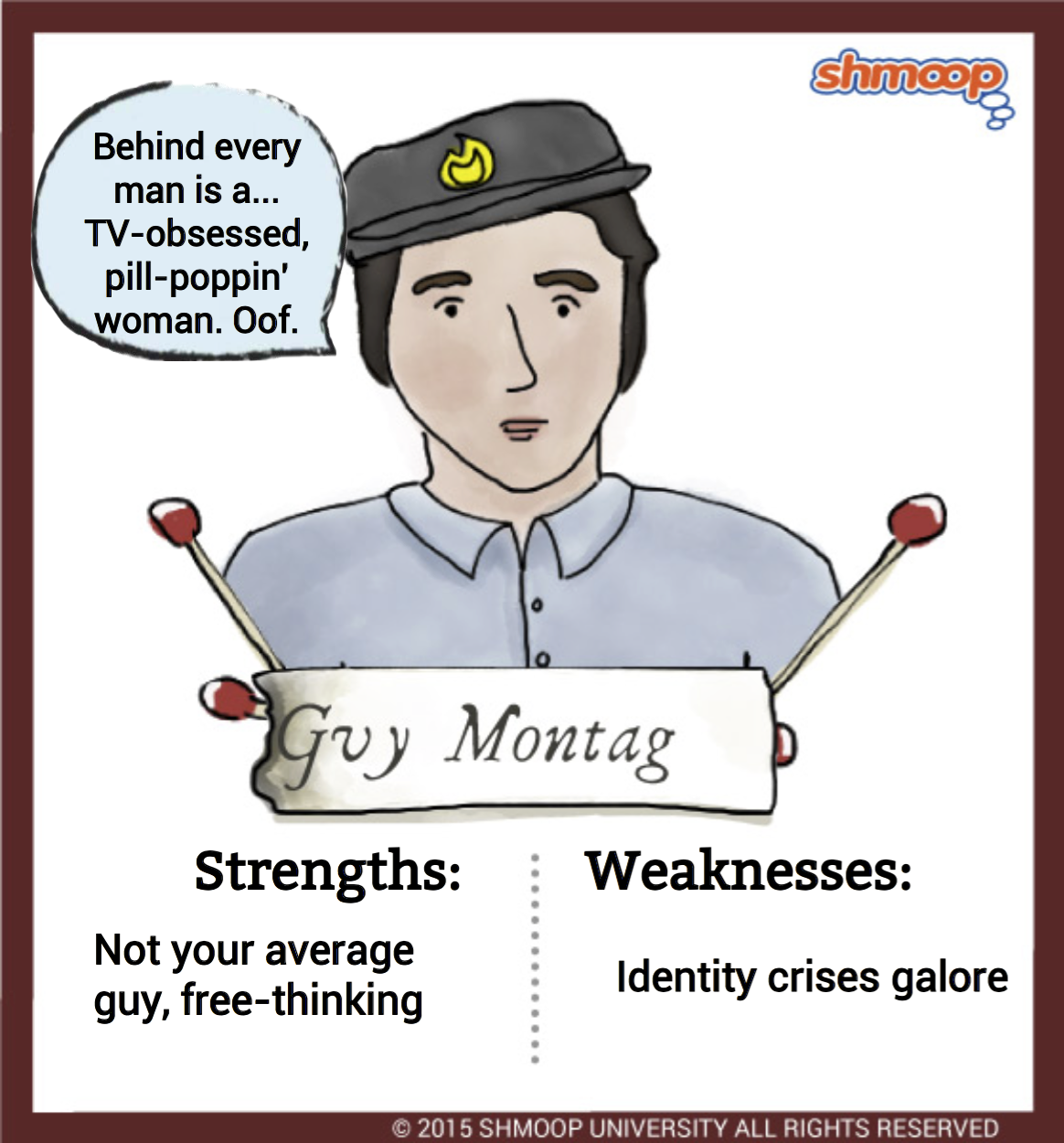

Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Not Your Ordinary Guy

He might have a pretty plain name, but Guy Montag is definitely not your average Joe. He has inklings that all is not right with his world even before he meets Clarisse, and his actions show it. For one, he doesn't turn in a clearly renegade individual (Faber, whom he met in the park spewing poetry), and he's been squirreling away books behind his ventilator grill for quite some time now. He's inquisitive, intelligent, and free-thinking. Good for him, right?

Wrong.

In his world, these traits are all highly illegal. Montag can't stand around congratulating himself for being an individual. In his mind, he's a traitor. Even worse, he's a fireman traitor, which is essentially the same as being a dirty cop.

Midlife Crisis Much?

When you look at it from Montag's perspective, it's no wonder he basically bounces from one personal crisis to the next for most of the novel.

What kind of crises, you ask? When Montag can't deal with the guilt, he starts messing with his sense of self. That's right—the ol' identity crisis. It begins when Clarisse asks him if he's happy. Montag feels "his body divide itself […], the two halves grinding one upon the other." Montag imagines that his new, rebellious half isn't him at all, but is actually Clarisse. When he speaks, he imagines her talking through his mouth.

Later, when Faber ends up inside Montag's head via the earpiece, we see more confusion of identity. Montag even distances himself from his own hands, which in his mind are the dirty culprits breaking all the rules. His hands act, he doesn't. This is, of course, all about guilt. If Montag can ascribe his actions to Clarisse, or to Faber, or to his dirty hands, then he isn't responsible for his crimes. It's the classic "It wasn't me!" defense.

Ignorance Is Not Bliss

The other big crisis for Montag is simply not knowing. He's unhappy, but he doesn't know why. He's confused about his relationship with Mildred. Does he love her? He's left with a vague dissatisfaction he can't shake because he doesn't know the source and is even further from a solution. "I'm going to do something," he tells his wife. "I don't even know what yet, but I'm going to do something big." So Montag turns to books in the belief that they hold all the answers. Surely they will cure his unhappiness.

Not so fast. As it turns out, books aren't actually everything. As Beatty points out, they're contradictory. They can't possibly hold the answers to life, or if they do, they're by no means serving them up on a silver platter. Because books present so many varying perspectives, it's up to the individual not just to read, but to read and think.

Of course, Montag has an inkling of as much by the time he gets to Faber, who he tells, "I don't want to change sides and just be told what to do. There's no reason to change if I do that."

What Montag will soon learn is that wisdom is about experience as much as it is about intellect and knowledge. To become the man he is at the end of the novel—a man headed toward the city with some pretty revelatory thoughts—he has to leave behind the world of technology and head into the world of nature; he has to see his city bombed and pick himself up off the ground afterwards. In doing so, he experiences the very lesson he's been trying to learn since he first picked up that Bible from out behind the ventilator grate.

Lessons Learned

What exactly is that lesson? It's about cycles. It's all that "time to sew, time to reap" stuff. We talk about this more in our "What's Up With the Ending?" section, which you should most definitely check out.

Montag has learned that life is composed of a construction-destruction cycle NOT by reading it in the Bible, but by experiencing it. He used to think fire was destructive; then he sees it as a positive force (warming, not burning). He's seen books destroyed, now he sees them being rebuilt in the minds of Granger's gang. He's seen the city destroyed, and it is with hope that he gets off the ground and continues toward it—to complete the creation part of the cycle.

He may have read all this stuff in the Bible while riding the subway to Faber's, but he doesn't "get it" until the end of Part Three. It is here that Montag's character transformation is complete. He is now a beautiful (and well-read) butterfly.

Guy Montag's Timeline