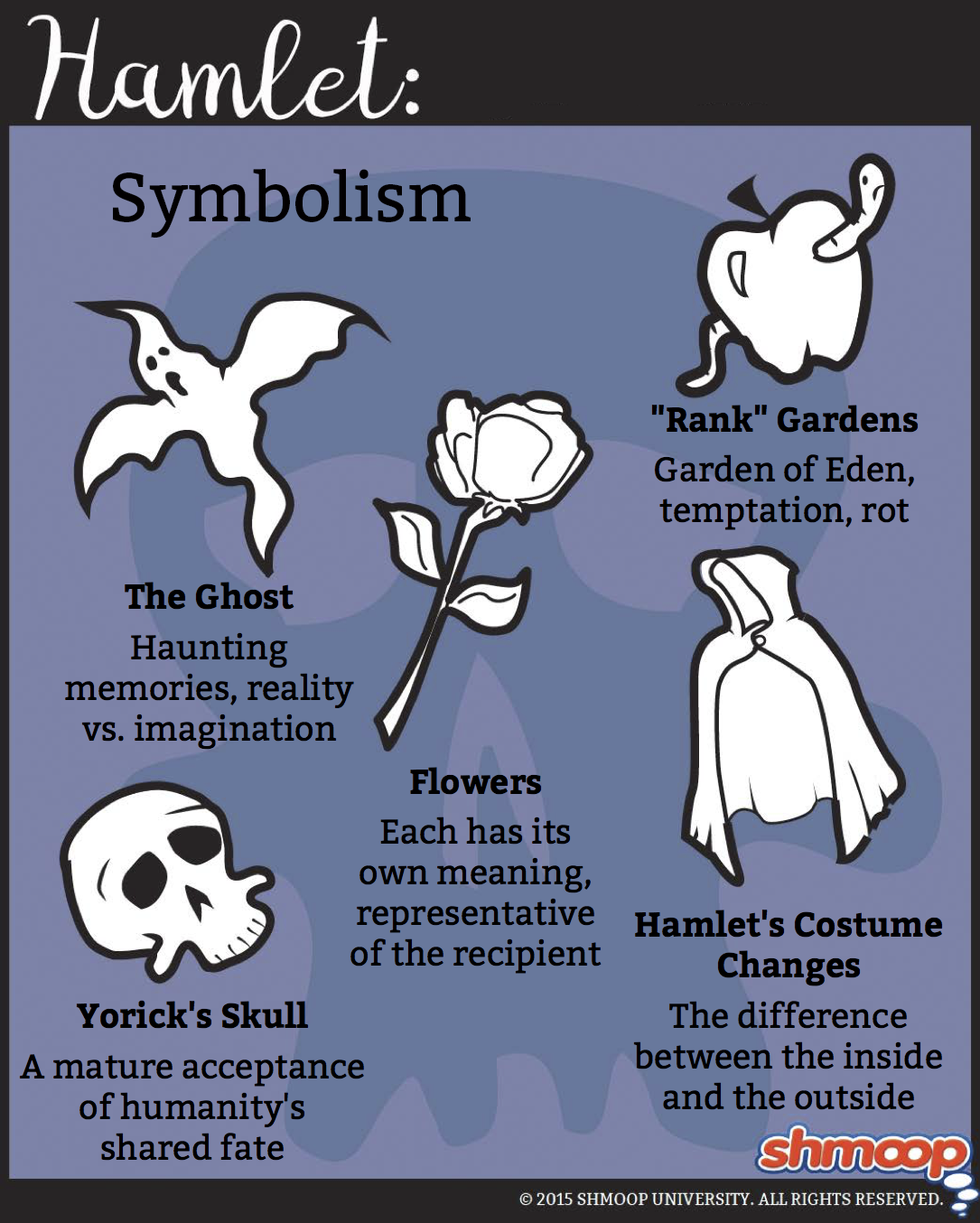

Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory

(Click the symbolism infographic to download.)

Early on in the play, we learn that Hamlet's all black get-up seems to be getting on his mom's nerves. (Good to know that some things haven't changed since 1600.) But why?

Well, Hamlet wears an "inky cloak" because he's in mourning for his dead father—but he's the only one in court still wearing black. Now that Claudius is king, the happy couple wants everyone to forget about Old Hamlet. So, Hamlet's black attire sets him apart from everyone else —just like his grief makes him an outsider in the cheerful court. (When the play's staged, Hamlet's black clothing really stands out, especially when the director positions him off to the side of stage while the rest of the court is in the center.)

But don't tell Hamlet that his clothes reflect his grief —he might jump down your throat, as he does here when his mom asks him why he "seems" so sad:

'Tis not alone my inky cloak, good mother,

Nor customary suits of solemn black,

Nor windy suspiration of forced breath,

No, nor the fruitful river in the eye,

Nor the dejected havior of the visage,

Together with all forms, moods, shapes of grief,

That can denote me truly (1.2.80-86)

In other words, Hamlet objects to the idea that any outward signs (dress, behavior, etc.) can truly "denote" what he's feeling on the inside (which is rotten). Hamlet's "suits of solemn black," he says, can't even begin to express his grief and anguish.

Later on, however, Hamlet changes his tune about what it is that clothing or costume can "denote." After he decides to play the role of an "antic" or madman, he does a costume change. Check out Ophelia's description of Hamlet:

My lord, as I was sewing in my closet,

Lord Hamlet, with his doublet all unbraced,

No hat upon his head, his stockings fouled,

Ungartered, and down-gyvèd to his ankle,

Pale as his shirt; his knees knocking each other,

And with a look so piteous in purport

As if he had been loosèd out of hell

To speak of horrors—he comes before me. (2.1.87-94)

If we assume that Hamlet makes himself appear disheveled in order to convince Ophelia that he's lost his mind, then we can also assume that Hamlet is banking on the convention that one's physical attire is a reflection of one's state of mind. And it works. Ophelia and Polonius are convinced that Hamlet is mad.

At the same time, we know (at least, we think we know) that Hamlet isn't really mad. So is he right after all, that clothes don't indicate anything about the state of mind? If he is—and we suspect that he is—then this is a pretty mind-blowing statement for Shakespeare to make: there can be a difference between the outside and the inside. And that difference, dear Shmoopers, is called interiority.

Welcome to the next 400+ years of literature.