Controversial Cousins

Four invertebrate phyla remain to be discussed: Phoronida, Bryozoa, Brachiopoda, and Echinodermata.

While these three phyla are often grouped together as lophophores, more recent molecular evidence suggests that these phyla may have more in common with flatworms, rotifers, mollusks, and annelids (which don't have lophophores). What these groups do have in common is a trochophore stage of life. A trochophore is a type little, swimming larvae that morphs into the adult form. Together, this gives us a big group of invertebrates that have either a lophophore or a trochophore. Collectively, these guys are referred to as the Lophotrochozoa.

Let's look at the phyla one by one.

Phoronids are the tubeworms. You might see them if you take a submarine trip to the bottom of the ocean. They make their tube out of chitin, the same substance in arthropod exoskeletons. They attach themselves to the sea floor and stick their lophophore out of the tube to catch food particles in the water. If threatened, they pull their soft tentacles inside their tube.

Image from here.

Bryozoa means "moss animal." They live in clone colonies that share an exoskeleton. (The clones are called zooids.) They use their lophophore to strain food particles out of the water like the tubeworms. They have a lot in common with the Phoronids, except that they work cooperatively in colonies.

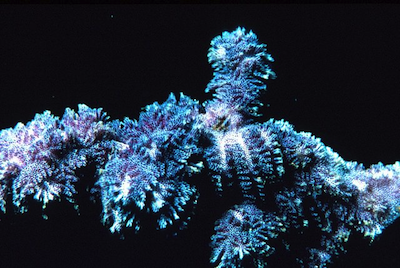

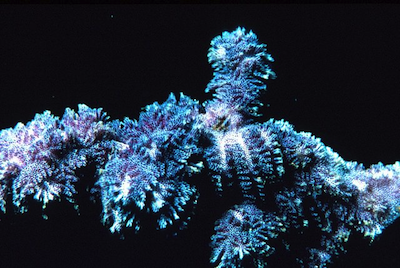

Attack of the clone colony. Image from here.

Brachiopoda, also called lampshells, look a bit like clams, with two outer shells. Unlike clams and other bivalves, though, each half of the Brachiopoda shell is symmetrical—but the top and bottom shells are different from each other. Bivalve shells aren't symmetrical and the two shells do mirror each other. Brachiopods use a muscular foot, called a pedicle, to move around, while mollusks use a thread-like foot structure. And, of course, brachiopods have a lophophore and mollusks don't.

A brachiopod called a lingula. The white translucent appendage is the pedicle.

Image from here.

This demonstrates an important point. Evolution is not a straight line, and not every common feature implies a common relationship. Ancestral echinoderms had bilateral or no symmetry, but somewhere along the way, having slightly more radial symmetry became advantageous, so it re-emerged..

The radial symmetry of echinoderms isn't like that of the radiata. It's usually in the form of five spokes. Echinoderms also differ in that they have an endoskeleton of plates and spines underneath the skin (enter the hedgehog). This makes them look spiky on the outside, but without a shell.

Another unique feature of echinoderms is a water vascular system. This system of water-filled vessels runs from the center out, ending in tube feet that act like little suckers. The pressure in this system is what moves the animal. Despite how it might sound, this isn't a wimpy system. Sea stars can pull apart mollusks using those water-powered tube feet.

Check out tube feet in action and some pretty worried clams.

Echinoderms have male and females forms, and their fertilization is usually external. External fertilization is when the eggs and sperm meet outside the animal. In the case of sea stars, males and females release eggs and sperm into the water, where they meet up to make baby sea stars.

Echinoderms go through metamorphosis, starting out as a bilateral embryo that settles on the floor to grow. The embryo then develops into free-floating larva that grows into the adult form. It ends up on the sea floor again, but this time, it can move. Some echinoderms can also reproduce asexually by splitting themselves apart.

Lost an arm? No biggie, make a new one. Many echinoderms can regenerate parts and may even give them up on purpose to escape a predator. Check out the sea cucumber spilling its guts to save its skin.

Echinoderms range from filter feeders to grazers to hunters, but all live on the ocean floor. This is the largest phylum of animals to have only marine species.

Lophophores

Phoronida, Bryozoa, and Brachiopoda have in one thing in common that no one else has: a lophophore. This is a specialized feeding structure that forms a ring or coil of tentacles surrounding the mouth. These aren't like the tentacles we've seen before. These tentacles are hollow extensions of the coelom and have cilia on them. The anus is just outside the mouth, putting both ends of the digestive system at one end. Lovely mental picture, isn't it?While these three phyla are often grouped together as lophophores, more recent molecular evidence suggests that these phyla may have more in common with flatworms, rotifers, mollusks, and annelids (which don't have lophophores). What these groups do have in common is a trochophore stage of life. A trochophore is a type little, swimming larvae that morphs into the adult form. Together, this gives us a big group of invertebrates that have either a lophophore or a trochophore. Collectively, these guys are referred to as the Lophotrochozoa.

Let's look at the phyla one by one.

Phoronids are the tubeworms. You might see them if you take a submarine trip to the bottom of the ocean. They make their tube out of chitin, the same substance in arthropod exoskeletons. They attach themselves to the sea floor and stick their lophophore out of the tube to catch food particles in the water. If threatened, they pull their soft tentacles inside their tube.

Image from here.

Bryozoa means "moss animal." They live in clone colonies that share an exoskeleton. (The clones are called zooids.) They use their lophophore to strain food particles out of the water like the tubeworms. They have a lot in common with the Phoronids, except that they work cooperatively in colonies.

Attack of the clone colony. Image from here.

Brachiopoda, also called lampshells, look a bit like clams, with two outer shells. Unlike clams and other bivalves, though, each half of the Brachiopoda shell is symmetrical—but the top and bottom shells are different from each other. Bivalve shells aren't symmetrical and the two shells do mirror each other. Brachiopods use a muscular foot, called a pedicle, to move around, while mollusks use a thread-like foot structure. And, of course, brachiopods have a lophophore and mollusks don't.

A brachiopod called a lingula. The white translucent appendage is the pedicle.

Image from here.

Echinodermata

Echinodermata means "hedgehog skin" and the creatures in this phylum don't disappoint. Sea stars, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers break a few rules. They're rebels without a head. Echinoderms have radial symmetry and no head, despite being part of the larger Bilateria branch of the animal family tree. Radial symmetry reappeared in the family tree, evolving from a bilateral ancestor.This demonstrates an important point. Evolution is not a straight line, and not every common feature implies a common relationship. Ancestral echinoderms had bilateral or no symmetry, but somewhere along the way, having slightly more radial symmetry became advantageous, so it re-emerged..

The radial symmetry of echinoderms isn't like that of the radiata. It's usually in the form of five spokes. Echinoderms also differ in that they have an endoskeleton of plates and spines underneath the skin (enter the hedgehog). This makes them look spiky on the outside, but without a shell.

Another unique feature of echinoderms is a water vascular system. This system of water-filled vessels runs from the center out, ending in tube feet that act like little suckers. The pressure in this system is what moves the animal. Despite how it might sound, this isn't a wimpy system. Sea stars can pull apart mollusks using those water-powered tube feet.

Check out tube feet in action and some pretty worried clams.

Echinoderms have male and females forms, and their fertilization is usually external. External fertilization is when the eggs and sperm meet outside the animal. In the case of sea stars, males and females release eggs and sperm into the water, where they meet up to make baby sea stars.

Echinoderms go through metamorphosis, starting out as a bilateral embryo that settles on the floor to grow. The embryo then develops into free-floating larva that grows into the adult form. It ends up on the sea floor again, but this time, it can move. Some echinoderms can also reproduce asexually by splitting themselves apart.

Lost an arm? No biggie, make a new one. Many echinoderms can regenerate parts and may even give them up on purpose to escape a predator. Check out the sea cucumber spilling its guts to save its skin.

Echinoderms range from filter feeders to grazers to hunters, but all live on the ocean floor. This is the largest phylum of animals to have only marine species.