Get a Backbone

When we think "animal," we usually think of a vertebrate. Sorry, we're a bit biased. We'll first look at what a chordate is and then at the earliest vertebrates, the fish.

Most chordates are also vertebrates, animals with a skeleton around the nerve cord. The vertebrae form from the notochord in the embryo. However, there are some invertebrate chordates. Subphylum Cephalochordata are the lancelets. Lancelets are marine-dwelling filter feeders. They spend a lot of time burrowed under the sand, tail end first. This is probably for protection. Lancelets occasionally change locales, wiggling from place to place.

Subphylum Urochordata are also called tunicates. They live in the ocean and most are sessile, attaching to things like rocks and boats. The adults don't look much like chordates. Their chordate features only exist in the larvae and disappear in the adult.

Tunicates are filter feeders. Water moves between two openings or siphons. Food is filtered out of water as it moves through the tunicate, which squeezes itself to force water through the siphons.

Watching a tunicate can be a bit like seeing one of your internal organs going out on a lark on its own.

Vertebrates can be divided into seven classes.

The first three classes are fish and the last four are called tetrapods, which means "four feet." The tetrapods all have four limbs, which could be wings, fins, or legs.

Fish have:

Need a new nightmare? Check out a lamprey mouth. Reminds us of Beetlejuice. Image from here.

The next stage in fish evolution included a few upgrades. First, fish got a jaw—which, to be super precise about it, is a skeletal structure that supports the mouth and helps in capturing prey. These fish also have paired fins on either side. Paired fins help fish swim faster. Scales are another new feature, adding protection.

Image from here

Sharks are made for speed. Their bodies look like muscular torpedoes, with pointed ends and thicker in the middle. This body shape is called fusiform and is common in animals that go fast in the water. Rays have a different shape. Rays are flattened and look a bit like swimming butterflies.

This group is carnivorous and very good at its job. Chondrichthyes skin is covered with scales shaped like little teeth that help streamline the fish, but are also abrasive. Sharks have rows and rows of very sharp teeth inside extremely strong-hinged jaws. They have lots of teeth and regrow them often. Some rays have poisonous tails, and the electric rays can discharge electrical shocks. Sounds like a dangerous crowd.

In addition to strong teeth, sharks have some powerful muscles. The larger sharks can maintain their body temperatures higher than the surrounding water, which keeps those muscles warm. Warmer muscles, up to a certain point, are more efficient, making sharks fast and strong. While attacks on humans by sharks or rays are very rare, these animals are extremely efficient killers.

Sharks and rays have developed sensory systems, completely tricked out for honing in on prey. They can see, hear, and smell. They can also sense electromagnetic fields produced by living organisms, a skill called electroreception. There are hundreds of electroreceptors on a shark or ray, and they allow the fish to sense even buried prey. A different set of organs on the sides of these animals, the lateral line system, can sense vibrations from other fish in the water.

Sharks and rays reproduce sexually, and as scientists have recently discovered, asexually too. Sharks are either male or female and their fertilization is internal. Some sharks bear live young and others lay eggs. Female sharks are also one of the few vertebrates that have been confirmed to reproduce through parthenogenesis.

Osteichthyes have paired fins, like sharks, but their fins can swivel around. This makes them very maneuverable. This is also very useful when there are sharks around.

Bony fishes are divided into three subclasses.

Image from here

What's a Chordate?

We are members of the phylum Chordata. Well, assuming that you're a human. What do we have in common with all chordates?- Notochord: stiff, but flexible, rod of tissue running along the whole animal

- Hollow nerve cord running above the notochord (top or dorsal side)

- Pharyngeal slits: openings around the windpipe

- Muscular tail (What, you don't see yours? We'll explain in a second.)

Most chordates are also vertebrates, animals with a skeleton around the nerve cord. The vertebrae form from the notochord in the embryo. However, there are some invertebrate chordates. Subphylum Cephalochordata are the lancelets. Lancelets are marine-dwelling filter feeders. They spend a lot of time burrowed under the sand, tail end first. This is probably for protection. Lancelets occasionally change locales, wiggling from place to place.

Subphylum Urochordata are also called tunicates. They live in the ocean and most are sessile, attaching to things like rocks and boats. The adults don't look much like chordates. Their chordate features only exist in the larvae and disappear in the adult.

Tunicates are filter feeders. Water moves between two openings or siphons. Food is filtered out of water as it moves through the tunicate, which squeezes itself to force water through the siphons.

Watching a tunicate can be a bit like seeing one of your internal organs going out on a lark on its own.

The Vertebrates

The third and final subphylum of the chordates is the Vertebrata. Vertebrates share the chordate characteristics above, plus a couple more.- Big heads. Vertebrates are highly cephalized. This means distinct brains and developed sensory organs on the head. A hard, skeletal, cranium encases the brain.

- A backbone. Stacked vertebrae make up an internal skeletal framework to support the animal and enclose the nerve cord.

- Two pairs of legs or other appendages.

- A skeleton inside that grows.

- Closed circulatory and excretory systems, with vessels to take blood to cells and vessels to get rid of waste.

- Two separate sexes. Vertebrates rely on sexual reproduction.

Vertebrates can be divided into seven classes.

| Class | Examples | |

| Fish | Agnatha | Jawless fish: lampreys |

| Chrondrichyes | Sharks, rays | |

| Osteichthyes | Bony fish: trout, salmon, tuna | |

| Tetrapods | Amphibia | Frogs, salamanders |

| Reptilia | Lizards, snakes, turtles | |

| Aves | Birds | |

| Mammals | Lions, tigers, bears, humans |

Here, Fishy Fish Fish

Let's start with the fish. All fish live in water, but only some animals in the water are fish. Fish get oxygen from the water. There are also mammals and reptiles in the ocean that breathe air.Fish have:

- Vertebrae and muscles that work on an internal skeleton

- Paired fins for swimming

- Scales and mucus on the outside to reduce friction

- A row of sensory organs down each side to detect changes in the water called the lateral line system

- Cannot control their body temperature, also called being cold-blooded

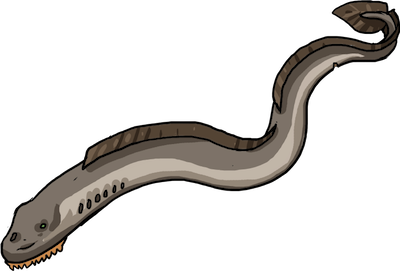

Agnatha

Modern lampreys are part of class Agnatha, which also includes hagfish. These animals eat other animals. Lampreys have jawless mouths with lots of teeth used to clamp onto living prey. Hagfish usually go after dead or weak animals and burrow inside, eating them from the inside out. Hagfish can cause huge problems for fishermen, eating whole catches of fish.

Need a new nightmare? Check out a lamprey mouth. Reminds us of Beetlejuice. Image from here.

The next stage in fish evolution included a few upgrades. First, fish got a jaw—which, to be super precise about it, is a skeletal structure that supports the mouth and helps in capturing prey. These fish also have paired fins on either side. Paired fins help fish swim faster. Scales are another new feature, adding protection.

Chondrichthyes

What do sharks and rays have in common with your nose? They are from the class Chondrichthyes, which means "cartilaginous fish." Cartilage is the flexible material that gives human noses and ears their shape. Sharks, rays, and skates don't have bones, but rather strong, flexible cartilage to support very powerful muscles.

Image from here

Sharks are made for speed. Their bodies look like muscular torpedoes, with pointed ends and thicker in the middle. This body shape is called fusiform and is common in animals that go fast in the water. Rays have a different shape. Rays are flattened and look a bit like swimming butterflies.

This group is carnivorous and very good at its job. Chondrichthyes skin is covered with scales shaped like little teeth that help streamline the fish, but are also abrasive. Sharks have rows and rows of very sharp teeth inside extremely strong-hinged jaws. They have lots of teeth and regrow them often. Some rays have poisonous tails, and the electric rays can discharge electrical shocks. Sounds like a dangerous crowd.

In addition to strong teeth, sharks have some powerful muscles. The larger sharks can maintain their body temperatures higher than the surrounding water, which keeps those muscles warm. Warmer muscles, up to a certain point, are more efficient, making sharks fast and strong. While attacks on humans by sharks or rays are very rare, these animals are extremely efficient killers.

Sharks and rays have developed sensory systems, completely tricked out for honing in on prey. They can see, hear, and smell. They can also sense electromagnetic fields produced by living organisms, a skill called electroreception. There are hundreds of electroreceptors on a shark or ray, and they allow the fish to sense even buried prey. A different set of organs on the sides of these animals, the lateral line system, can sense vibrations from other fish in the water.

Sharks and rays reproduce sexually, and as scientists have recently discovered, asexually too. Sharks are either male or female and their fertilization is internal. Some sharks bear live young and others lay eggs. Female sharks are also one of the few vertebrates that have been confirmed to reproduce through parthenogenesis.

Osteichthyes

Next in fish evolution, we get bones. Fish in the class Osteichthyes are the "bony fish." In addition to a hinged jaw and paired fins, they have a hard endoskeleton of calcium phosphate. Bony fishes also carry their own float inside, an air sac called a swim bladder. (This is not to be confused with a swim diaper. Completely different purpose.) Bony fishes can inflate and deflate this internal balloon to help them float.Osteichthyes have paired fins, like sharks, but their fins can swivel around. This makes them very maneuverable. This is also very useful when there are sharks around.

Bony fishes are divided into three subclasses.

- Lobe-finned: (Crossopterygii). These are fresh-water fish with muscular fins in the back that could be used a little like legs to push them along the bottom. There is one living descendant, the coelacanth.

Image from here

- Lungfishes: (Dipnopi). The name says it all—these fish have both lungs and gills and live in fresh water. Ancient lungfishes and lobefish may have used their leg-like fins and lungs to occasionally move on land. Lungfish can wait out dry seasons. They bury themselves, slow down their body functions to a bare minimum, and breathe air until better conditions arrive.

- Ray-finned: (Actinopterygii). The fins of these fish are supported by thin rays of bone in a fan shape. (Lobe-finned fish also have these, but their fins are thicker and you can't see the rays.) Ray-finned fish are found in both fresh and salt water and include lots of familiar ones, like salmon, trout, and eels. In terms of their numbers, this is the largest class of vertebrates.