Life Takes to the Land

We see arthropods everywhere we go. Arthropoda, the third protostome phylum, is everywhere. Arthropods live on the land and in the sea. They swim, run, and fly. Arthropods mean a lot to us, too. We eat them, get sick from them, and chase them with flyswatters and bug spray. Some are pollinators, crucial to the survival of plants that are crucial to us. Some spread disease among us and the animals and plants we raise. We may sometimes want to, but we can't live without arthropods.

Arthropods are the most successful animals on earth, with both the most individuals and the most species around. They are also the first animals to come ashore and the first to fly. Life on earth evolved in the water and still depends upon it. Arthropods were to the first to figure out how to survive on dry land by: 1) not drying out by evolving an exoskeleton and 2) getting oxygen without water by breathing air.

The bark scorpion. Wonder if his bite is worse. Image from here.

Insects, arachnids, and crustaceans are all arthropods. Here are some things they have in common:

Arthropods are divided into five sub-phyla. Within these are many classes of arthropods that have similar characteristics.

Over time, arthropod bodies became more modified. Many segments fused into fewer and body functions became more specialized to specific segments. Repeated, paired legs remained, but not all legs are the same.

Image from here.

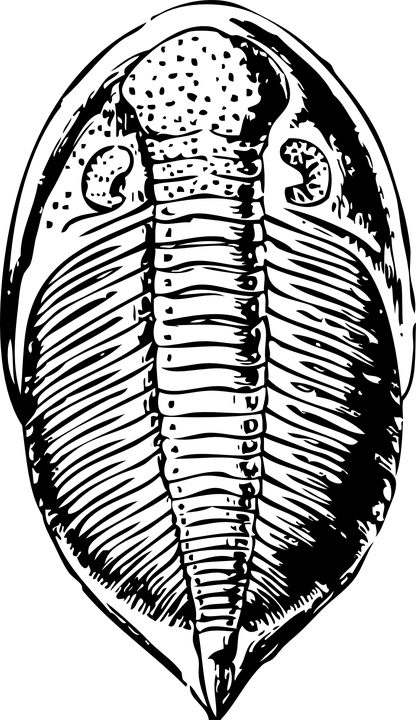

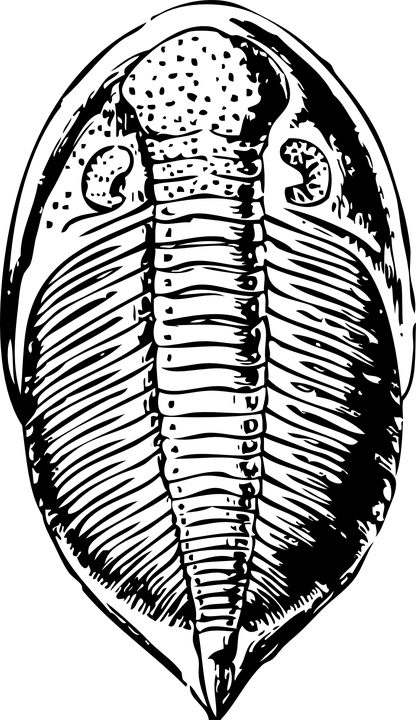

Even though they don't look like much, trilobites are important for what we know about evolution and the history of Earth. Trilobite fossils in rocks tell us how old the rocks are, since we know trilobites all lived during the Cambrian period 500 million years ago.

Image from here.

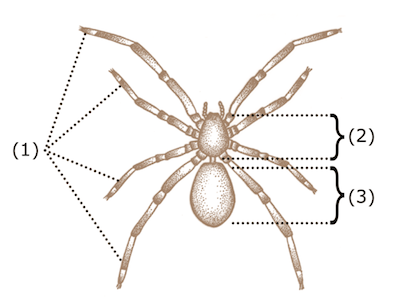

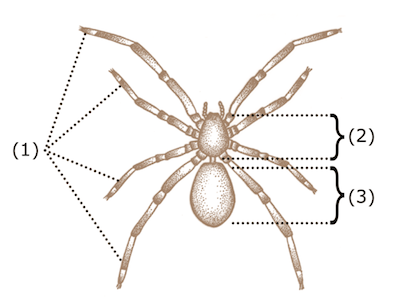

Here is the basic anatomy of a spider:

(1) Four pairs of legs, (2) Cephalothorax, and (3) Abdomen. Image from here.

The first two parts of the basic arthropod body are fused in a spider, creating a cephalothorax, a fancy word for head and thorax. If we look more at the inside of a Chelicerate, in this case a spider, we can see how differentiated the segments are. In other words, different parts of the body specialize in different things. Don't worry too much about learning the individual parts, but instead, marvel at the complexity of this creepy crawly.

Chelicerates have a unique way to breathe. Spiders and scorpions on land have book lungs and horseshoe crabs in the water have book gills. Book lungs and gills look like the stacks of pages you see on the unbound side of a book. The "pages" are layers of tissue with spaces in between. There is a small opening to the outside so air can flow into the spaces.

Hemolymph flows through the tissue and gases are exchanged between the hemolymph and the open spaces. Having lots of spaces means more surface area for more gas exchange. This all happens inside the exoskeleton of a land chelicerate to keep moisture inside. Marine chelicerates have gills structured similarly, but because they are in water, the structure is on the outside of the animal.

There are two classes of animals in this subphylum: Arachnida (spiders, ticks, scorpions, mites) and Merostomata (horseshoe crabs).

Horseshoe crabs are funky animals that aren't really crabs; they just look kind of like them. A shell covers them, but unlike crustaceans and some of the other shelled creatures we've met, they have two eyes that stick out the front, a tail that sticks out the back, and eight jointed legs underneath. They actually have ten eyes, but the others are under the shell (or carapace). The two eyes on top are compound eyes—meaning they're made of many lenses that produce images. The other eyes are light sensors.

Spiders, ticks, mites, and scorpions are arachnids. These are the creatures of our nightmares. (Arachnophobia, anyone?) Most are carnivorous. They can vary in size from tiny mites to Aragog. Well, actually, no, but J.K. Rowling wasn't as far off as we'd like.

Arachnids are generally hunters. They have modified chelicerae, with poison glands and a pointy end for injecting it into prey. Spiders have a famous adaptation for catching prey as well: webs. Silk glands in their abdomen secrete a liquid protein that comes out through spinnerets and then dries immediately in the air to form strands.

Spiders make webs with these strands, and each species has a distinctive web pattern. Silk also comes in handy for dropping lines to escape predators, tying up prey in the web, and covering eggs. They're also useful for fighting the Green Goblin. Unfortunately for little pigs, they can't really write messages with it.

Here's a juicy fact. Spiders can't chew, so don't expect them to be great dinner guests. After they've attacked prey, they drool digestive fluid onto their victim, which dissolves it. They then drink their prey.

Ticks and mites are parasitic arachnids. They feed only on blood and attack their prey by cutting a hole into the skin and sticking a mouthpart (called a hypostome) into the newly created incision to drink its blood. This doesn't usually harm the host, except when the tick is carrying a disease.

Ticks can cause Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Lyme disease. Gross. Image from here.

Scorpions add to the legend of scary arachnids. They look a bit like crabs, with large claws on the front legs, but have a tail that arches up over the back to face forward and show off a large stinger. Scorpions have three parts, adding a tail to the arachnid cephalothorax and abdomen. The claws are much bigger than those of spiders, horseshoe crabs, and ticks.

Arachnids reproduce sexually. Yes, it's true that the females of some spider species eat the male at during or after mating. Male spiders use their front appendages to transmit sperm to the female, who later lays eggs. Spider moms may protect their eggs until hatching, though some spider moms die after laying eggs. Think Charlotte's Web (again).

Image from here.

Crustaceans have two to three body segments and jointed legs, as do all arthropods. Crustaceans, however, have a unique leg structure. The rest of the arthropods have legs made up of segments that lie end to end. Crustacean legs can have one leg segment that attaches to two more, giving them a sort of specialized foot. This leg is called biramous, meaning "two branches."

Where spiders had chelicerae for a mouth, crustaceans have mandibles. Mandibles are modified appendages right at the mouth that crunch up food. Crustaceans bite—don't ask how we know. *shudder*

Crustaceans generally have male and female individuals, but many can also reproduce through parthenogenesis. This is when females produce eggs that grow into viable adults without needing sperm. Poor crustacean men—they really hit the glass ceiling in the arthropod world.

The largest group of crustaceans is the copepods, which aren't as well known as their tasty cousins. Copepods are everywhere in fresh and salt water. They're teeny-tiny, but big in their impact. Animals from fish to whales depend upon copepods as food. Copepods depend upon algae and microscopic plants for their food, making them the first animal in the food chain.

Millipedes live on land and eat decaying plants. A millipede ancestor may have been the first creature on land. Image from here.

Centipedes are millipedes' tough cousins. Centipedes are carnivorous, and their front pair of appendages are toxic claws that inject venom into their prey. Centipedes can be harmful to humans. Centipede means "one hundred legs," though the number of legs varies widely between species. Some have only 15 pairs of legs, while others can have over 150 pairs. Centipedes will always have one pair of legs per body segment, though.

They may be small, but up close, these 'pedes look very tough.

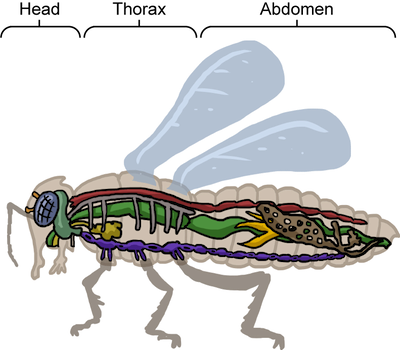

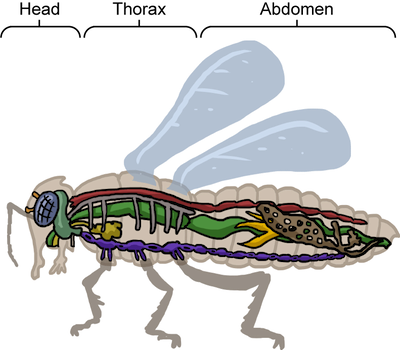

Insects are arthropods and have three body parts, but add a whole new structure—wings. Insects may have one or two pairs of them. The wings are not modified, segmented appendages, but outgrowths of the exoskeleton (in contrast to bird and bat wings). Insects also have three pair of legs coming from the thorax.

Insect features:

Insects have also developed a wide range of ways to eat. Mouthparts are highly modified and may bite, suck, or pierce depending on the insect and its food. If something exists, there's probably an insect that eats it.

Insects have specialized organ systems. As with all arthropods, insects have an open circulatory system. The digestive system has different parts specialized for various aspects of breaking down food. The lower part of the digestive system sports Malpighian tubes, which take waste out of the body. For respiration, insects use a system of trachea (Greek for "windpipe"), tubes that branch throughout the body and link to pores in the exoskeleton (spiracles).

Insects have males and females and fertilization is internal. Insects lay eggs, often only once in a lifetime. Most insects go through some kind of metamorphosis, with the young larvae starting out with a different body form from an adult. Check out this time-lapse video of a monarch caterpillar metamorphosing.

With insects, we get the first examples of social behavior, where members of a species live and work together. Most insects are solitary, but some (like ants, bees, and termites) exhibit complex social behavior. There are even different physical forms for different purposes within the group.

There are about 26 orders of insects, which comprise over one million known species. Scientists think that there could be another 30 million species yet to be discovered.

Insects were the first creatures to evolve flight and the only invertebrates to do it. This allowed them to take over whole new environments. Flying insects can disperse quickly and range widely to find what they need: food, mates, or someplace to live. Insects really began to diversify when flight evolved and continued to diversify with the success of flowering plants.

Insects eat and pollinate most of the plants on earth. While we often think of insects as pests, spreading disease and destroying our food crops, without insects we wouldn't have those food crops in the first place.

Arthropods are the most successful animals on earth, with both the most individuals and the most species around. They are also the first animals to come ashore and the first to fly. Life on earth evolved in the water and still depends upon it. Arthropods were to the first to figure out how to survive on dry land by: 1) not drying out by evolving an exoskeleton and 2) getting oxygen without water by breathing air.

The bark scorpion. Wonder if his bite is worse. Image from here.

Insects, arachnids, and crustaceans are all arthropods. Here are some things they have in common:

- Bilateral symmetry. This means a front, back, top, bottom, left and right sides.

- Segmented body plans, often with legs on each segment except the head. Their bodies are divided into sections and there are legs almost everywhere.

- Many pairs of jointed legs (in fact, arthropod means "jointed foot"). Arthropod legs have more than one section and the legs bend where the sections meet.

- Body segments specialized for specific functions. The segmented worms tend to have functions repeated in each section. The segments of an arthropod each do a different thing. Arthropods generally have two to three body parts called tagmata (sections of the body made up of fused segments).

- Rigid, non-growing exoskeletons made from chitin and protein. Higher animals have their bones on the inside, but arthropods have their skeleton on the outside.

- Growth through molting. The hard exoskeleton has to come off and be grown again when the arthropod outgrows the old one. Molting really is as inconvenient as it sounds. The arthropod is exposed during this process and uses a lot of energy to re-grow a skeleton.

- Open circulatory system. We've seen this before with mollusks, but it works a little differently in arthropods. Instead of fluid flowing around the main body cavity (coelom), arthropods have small cavities called hemocoel around specific organs. The heart pumps a blood-like fluid called hemolymph through the hemocoel.

- A centralized nervous system. Arthropods have a nervous system that looks a bit like a ladder. The brain is in the head and two nerve cords run through the body, which are connected in each segment. Each segment has a connected pair of ganglia, which are larger bundles of nerve tissue that control certain functions in that segment.

- Heads with developed sensory organs like eyes and antennae. The head is the place with most of the tools for figuring out what's going on outside the animal. Many arthropods have setae, which are bristles that sense movement in the environment around them. They also have eyes or other ways to detect light, as well as organs to sense chemicals and vibrations.

- Depending on the habitat, arthropods have a variety of systems for breathing. Crustaceans living underwater have gills. Spiders have their own version of lungs to get oxygen from the air. Insects have a system of tracheae (tubes) that run directly to the cells from pores in the surface called spiracles.

- Reproduce sexually and (usually) have male and female forms. Aquatic arthropods use both external and internal fertilization, depending on the species. The external-internal issue concerns whether sperm and egg meet inside the female or outside. Arthropods who live on land generally use internal fertilization or have a means to protect sperm from dying out before it reaches the female.

- Change from one form to another through metamorphosis. Arthropods are transformers. As they grow, they go from crawling to flying, or from looking like a blob to looking like a lobster. A baby insect does not look like its parents. Caterpillars change into butterflies and lobster larvae change into beautiful, tasty creatures.

Arthropods are divided into five sub-phyla. Within these are many classes of arthropods that have similar characteristics.

Trilobitomorpha

Trilobites were a large group of marine arthropods that became extinct before the dinosaurs were around. (That's a handy reminder that arthropods are older than any vertebrates. Respect your elders!) They looked a little like the chitons and like some current arthropods such as pill bugs, which you may know as roly-polys. Trilobites had a head and then many repeated segments, with a couple legs on each segment. The legs were pretty much all the same.Over time, arthropod bodies became more modified. Many segments fused into fewer and body functions became more specialized to specific segments. Repeated, paired legs remained, but not all legs are the same.

Image from here.

Even though they don't look like much, trilobites are important for what we know about evolution and the history of Earth. Trilobite fossils in rocks tell us how old the rocks are, since we know trilobites all lived during the Cambrian period 500 million years ago.

Chelicerata

The Chelicerata, meaning "claw horns," includes spiders, scorpions, mites, and horseshoe crabs. This group is named for its mouth. Their mouthparts are modified legs that have claws to bring food into the mouth. The green parts in this picture of a spider's head are the chelicerae.

Image from here.

Here is the basic anatomy of a spider:

(1) Four pairs of legs, (2) Cephalothorax, and (3) Abdomen. Image from here.

The first two parts of the basic arthropod body are fused in a spider, creating a cephalothorax, a fancy word for head and thorax. If we look more at the inside of a Chelicerate, in this case a spider, we can see how differentiated the segments are. In other words, different parts of the body specialize in different things. Don't worry too much about learning the individual parts, but instead, marvel at the complexity of this creepy crawly.

Chelicerates have a unique way to breathe. Spiders and scorpions on land have book lungs and horseshoe crabs in the water have book gills. Book lungs and gills look like the stacks of pages you see on the unbound side of a book. The "pages" are layers of tissue with spaces in between. There is a small opening to the outside so air can flow into the spaces.

Hemolymph flows through the tissue and gases are exchanged between the hemolymph and the open spaces. Having lots of spaces means more surface area for more gas exchange. This all happens inside the exoskeleton of a land chelicerate to keep moisture inside. Marine chelicerates have gills structured similarly, but because they are in water, the structure is on the outside of the animal.

There are two classes of animals in this subphylum: Arachnida (spiders, ticks, scorpions, mites) and Merostomata (horseshoe crabs).

Horseshoe crabs are funky animals that aren't really crabs; they just look kind of like them. A shell covers them, but unlike crustaceans and some of the other shelled creatures we've met, they have two eyes that stick out the front, a tail that sticks out the back, and eight jointed legs underneath. They actually have ten eyes, but the others are under the shell (or carapace). The two eyes on top are compound eyes—meaning they're made of many lenses that produce images. The other eyes are light sensors.

Spiders, ticks, mites, and scorpions are arachnids. These are the creatures of our nightmares. (Arachnophobia, anyone?) Most are carnivorous. They can vary in size from tiny mites to Aragog. Well, actually, no, but J.K. Rowling wasn't as far off as we'd like.

Arachnids are generally hunters. They have modified chelicerae, with poison glands and a pointy end for injecting it into prey. Spiders have a famous adaptation for catching prey as well: webs. Silk glands in their abdomen secrete a liquid protein that comes out through spinnerets and then dries immediately in the air to form strands.

Spiders make webs with these strands, and each species has a distinctive web pattern. Silk also comes in handy for dropping lines to escape predators, tying up prey in the web, and covering eggs. They're also useful for fighting the Green Goblin. Unfortunately for little pigs, they can't really write messages with it.

Here's a juicy fact. Spiders can't chew, so don't expect them to be great dinner guests. After they've attacked prey, they drool digestive fluid onto their victim, which dissolves it. They then drink their prey.

Ticks and mites are parasitic arachnids. They feed only on blood and attack their prey by cutting a hole into the skin and sticking a mouthpart (called a hypostome) into the newly created incision to drink its blood. This doesn't usually harm the host, except when the tick is carrying a disease.

Ticks can cause Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Lyme disease. Gross. Image from here.

Scorpions add to the legend of scary arachnids. They look a bit like crabs, with large claws on the front legs, but have a tail that arches up over the back to face forward and show off a large stinger. Scorpions have three parts, adding a tail to the arachnid cephalothorax and abdomen. The claws are much bigger than those of spiders, horseshoe crabs, and ticks.

Arachnids reproduce sexually. Yes, it's true that the females of some spider species eat the male at during or after mating. Male spiders use their front appendages to transmit sperm to the female, who later lays eggs. Spider moms may protect their eggs until hatching, though some spider moms die after laying eggs. Think Charlotte's Web (again).

Crustacea

Crustaceans include some of the favorite food items of many other animals, including humans: crabs, lobsters, shrimp, barnacles, and krill. Crustaceans live primarily in the ocean, though there are freshwater ones too, like crayfish. Most move around using ten pairs of legs. Barnacles, however, are sessile and use their six pairs of legs to grab prey.

Image from here.

Crustaceans have two to three body segments and jointed legs, as do all arthropods. Crustaceans, however, have a unique leg structure. The rest of the arthropods have legs made up of segments that lie end to end. Crustacean legs can have one leg segment that attaches to two more, giving them a sort of specialized foot. This leg is called biramous, meaning "two branches."

Where spiders had chelicerae for a mouth, crustaceans have mandibles. Mandibles are modified appendages right at the mouth that crunch up food. Crustaceans bite—don't ask how we know. *shudder*

Crustaceans generally have male and female individuals, but many can also reproduce through parthenogenesis. This is when females produce eggs that grow into viable adults without needing sperm. Poor crustacean men—they really hit the glass ceiling in the arthropod world.

The largest group of crustaceans is the copepods, which aren't as well known as their tasty cousins. Copepods are everywhere in fresh and salt water. They're teeny-tiny, but big in their impact. Animals from fish to whales depend upon copepods as food. Copepods depend upon algae and microscopic plants for their food, making them the first animal in the food chain.

Myrapodia: Chilopoda and Diplopoda

This section is all about the millipedes (class Diplopoda) and the centipedes (class Chilopoda). Millipedes look like armored, segmented worms with lots of legs. Their name means "a million legs," but it only looks like a million. There are two pairs of legs on each body segment, which can make up to a few hundred legs, depending on the species.

Millipedes live on land and eat decaying plants. A millipede ancestor may have been the first creature on land. Image from here.

Centipedes are millipedes' tough cousins. Centipedes are carnivorous, and their front pair of appendages are toxic claws that inject venom into their prey. Centipedes can be harmful to humans. Centipede means "one hundred legs," though the number of legs varies widely between species. Some have only 15 pairs of legs, while others can have over 150 pairs. Centipedes will always have one pair of legs per body segment, though.

They may be small, but up close, these 'pedes look very tough.

Hexapoda: Insecta

Insects (class Insecta) are everywhere on land and fresh water. They live fast and furious, spreading everywhere and reproducing quickly and in quantity.Insects are arthropods and have three body parts, but add a whole new structure—wings. Insects may have one or two pairs of them. The wings are not modified, segmented appendages, but outgrowths of the exoskeleton (in contrast to bird and bat wings). Insects also have three pair of legs coming from the thorax.

Insect features:

- Hard exoskeleton

- Segmented body

- Six legs in three pairs

- Compound eyes

- Three body parts

- Many have wings

- One pair of antennae on the head

Insects have also developed a wide range of ways to eat. Mouthparts are highly modified and may bite, suck, or pierce depending on the insect and its food. If something exists, there's probably an insect that eats it.

Insects have specialized organ systems. As with all arthropods, insects have an open circulatory system. The digestive system has different parts specialized for various aspects of breaking down food. The lower part of the digestive system sports Malpighian tubes, which take waste out of the body. For respiration, insects use a system of trachea (Greek for "windpipe"), tubes that branch throughout the body and link to pores in the exoskeleton (spiracles).

Insects have males and females and fertilization is internal. Insects lay eggs, often only once in a lifetime. Most insects go through some kind of metamorphosis, with the young larvae starting out with a different body form from an adult. Check out this time-lapse video of a monarch caterpillar metamorphosing.

With insects, we get the first examples of social behavior, where members of a species live and work together. Most insects are solitary, but some (like ants, bees, and termites) exhibit complex social behavior. There are even different physical forms for different purposes within the group.

There are about 26 orders of insects, which comprise over one million known species. Scientists think that there could be another 30 million species yet to be discovered.

Insects were the first creatures to evolve flight and the only invertebrates to do it. This allowed them to take over whole new environments. Flying insects can disperse quickly and range widely to find what they need: food, mates, or someplace to live. Insects really began to diversify when flight evolved and continued to diversify with the success of flowering plants.

Insects eat and pollinate most of the plants on earth. While we often think of insects as pests, spreading disease and destroying our food crops, without insects we wouldn't have those food crops in the first place.