Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Beth is one of those children in a novel who is so good and sweet and perfect that you just know she's going to die, because nothing interesting could ever happen to her, and anyone that angelic belongs in Heaven – like Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop or Li'l Eva in Uncle Tom's Cabin. OK, sorry if we spoiled that one for you, but seriously: Beth is happy and content at home, too shy to go to school or go out in the world, and spends her time doing sweet little things around the house to make her family, her pet cats, and even her dolls happy and comfortable. She's doomed. She has no ambitions, no desires, doesn't dream about getting married, and thinks about God and Heaven a lot. These are all the signs that a nineteenth-century author uses to tell you that a kid is not long for this world. The only thing that really surprises us is that she survives her first bout of scarlet fever and doesn't die until the second half of the novel.

Beth's only earthly love is music. She adores playing the piano and singing, and the only material thing that she wants is a nicer piano, since her family's is old and out of tune. The piano that she longs for is provided by her wealthy neighbor, old Mr. Laurence, who gives her his dead granddaughter's old piano. If you were still missing out on the signs that Beth is going to die, then you should get suspicious when you find out that Beth reminds Mr. Laurence of the little granddaughter he had who died young. Beth shares this anonymous girl's musical talent – and, by the logic of the sentimental novel, she's also going to share her early demise. Of course, Beth's love of music isn't that earthly, either. She mostly sings hymns, and her connection to such an ethereal art form also reinforces the idea that she belongs in Heaven, not in the parlor.

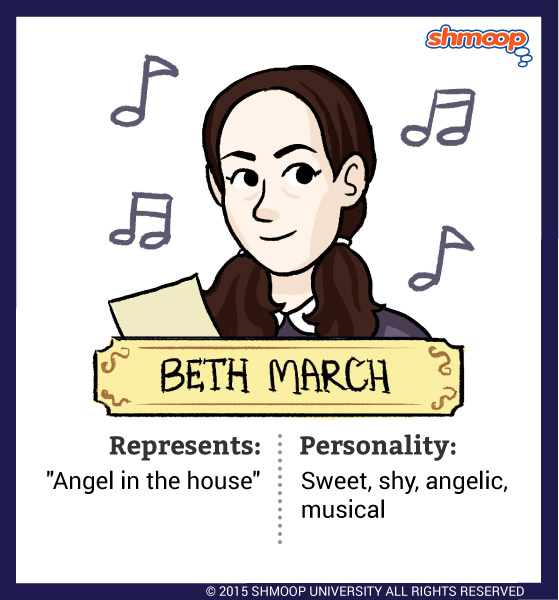

What we're trying to say is that Beth is the little-girl version of a nineteenth-century stock figure called the "angel in the house." The phrase "angel in the house" is the title of an 1854 poem by an author called Coventry Patmore. (If you're keeping score, that means the poem came out fourteen years before the first part of Little Women, so it was definitely circulating in popular culture when Alcott's novel appeared.) The poem itself is one of the few pieces of literature that we actually don't recommend – although you can read it here if you really want to – but basically it's about housewives, and how they should be these perfect, patient, personality-less, submissive domestic goddesses who make little safe nests for their hard-working hubbies and never, ever have opinions or needs of their own. The "angel in the house" figure defines everything that women were supposed to be in the latter half of the nineteenth century, and Beth, despite her youth and the fact that she doesn't get married, is definitely a sample of this tradition.

Just to be clear: we don't want to rag on housewives and other men and women who stay at home to take care of the family. The stay-at-home people we know work really hard and play a crucial role for their families and society. But, you know, we think they should be allowed to have opinions, and vote, and stuff, not just toss their curls and say "whatever you think, honey."

Anyway, back to Beth. Although she dies just as she reaches adulthood, Beth has a significant effect on the people around her, especially her sister, Jo. As Jo nurses Beth through her final illness, she realizes how important domestic duties really are. Jo resolves to take over Beth's role as the glue that holds her family together, caring for her parents and cherishing the everyday tasks that Beth did so lovingly. In this way, Beth's example lives on, although perhaps with a little more spice and a little less sugar.